This Substack is by David Perrine. I write about architecture, aesthetics, design theory, and philosophy. I share new posts weekly for paying subscribers and bi-weekly for free subscribers. If you enjoy my work, please consider supporting. It means a lot and it allows me to continue doing what I love: writing about architecture <3

Composition - a thing composed of various elements

To many, the word composition feels suspicious when used to discuss the organization of architectural spaces. The term feels at home when used to describe formal relationships in the more pure aesthetic fields. It feels off when used in design disciplines, where the organization should be dictated by function instead of the vague, subjective, or indulgent tendencies of composition.

Still, composition has remained an enduring idea in architectural theory beyond the design of ornament or facades. It has served as a valuable tool in designing spatial sequences, massings, floorplans, sections, and other part-to-whole relationships in the design of spaces and objects.

Different eras have developed their own strategies for composition, and understanding the various shifts in compositional theory speaks a lot to each epoch's culture and aesthetic tendencies.

This essay will focus on one of the more recent developments in the discourse of architectural composition, namely Venturi's 'Difficult Whole' which was first mentioned in his history book "Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture" Published in 1966. The book argues that the Modern era is defined by complexity and contradiction and that contemporary architecture should reflect these traits. It then notes that the ideas of complexity and contradiction are not necessarily new but could be found by looking back in time and in different mediums. The book uses a vast library of precedents to demonstrate the effects of the techniques of complexity and contradiction.

Paying subscribers can read my analysis of the first half of the book here:

Before jumping straight into Venturi's waiting arms, I will first discuss a brief history of composition in architecture. This is necessary because Venturi's ideas combine borrowed premodern concepts he synthesizes.

Classical Composition

Venturi's text draws mainly from Renaissance and Baroque theory. Although both artistic eras occurred close to each other in time, they are aesthetically antithetical.

In Renaissance theory, forms and figures are organized around the principle of order. Geometry is always proportionally logical, clear, and controlled. Symmetry, repetition, and hierarchy are dogmatically followed.

The theory of the Renaissance design ethic was best articulated by Heinrich Wolfflin in his seminal work "Renaissance and Baroque":

“Renaissance art is the art of calm and beauty. The beauty it offers us has a liberating influence, and we apprehend it as a general sense of well-being and a uniform enhancement of vitality... Each form has been born easily, free and complete. Its arches are pure semicircles; proportions are broad and pleasing. Everything breathes satisfaction”

(Wölfflin 38).

A noteworthy example of Renaissance composition in architecture is the Tempietto of San Pietro in Montorio by Donato Bramante.

It’s arches are semicircles. It’s plan and elevation is symmetrical on two axes. It’s form is stable and clear. Each element is symmetrical to itself and this can stand alone. The parts themselves compose a greater whole through hierarchy.

The Baroque on the other hand, maintains many of the same tools—symmetry, axiality, proportion—but directs them to different ends.

"Baroque aims at a different effect. It wants to carry us away with the force of its impact, immediate and overwhelming... It does not convey a state of present happiness, but a feeling of anticipation, of something yet to come, of dissatisfaction and restlessness rather than fulfilment... This general effect... results from a certain treatment of form which we shall now describe under the two main headings of ‘massiveness’ and ‘movement’”

(Wölfflin 38).

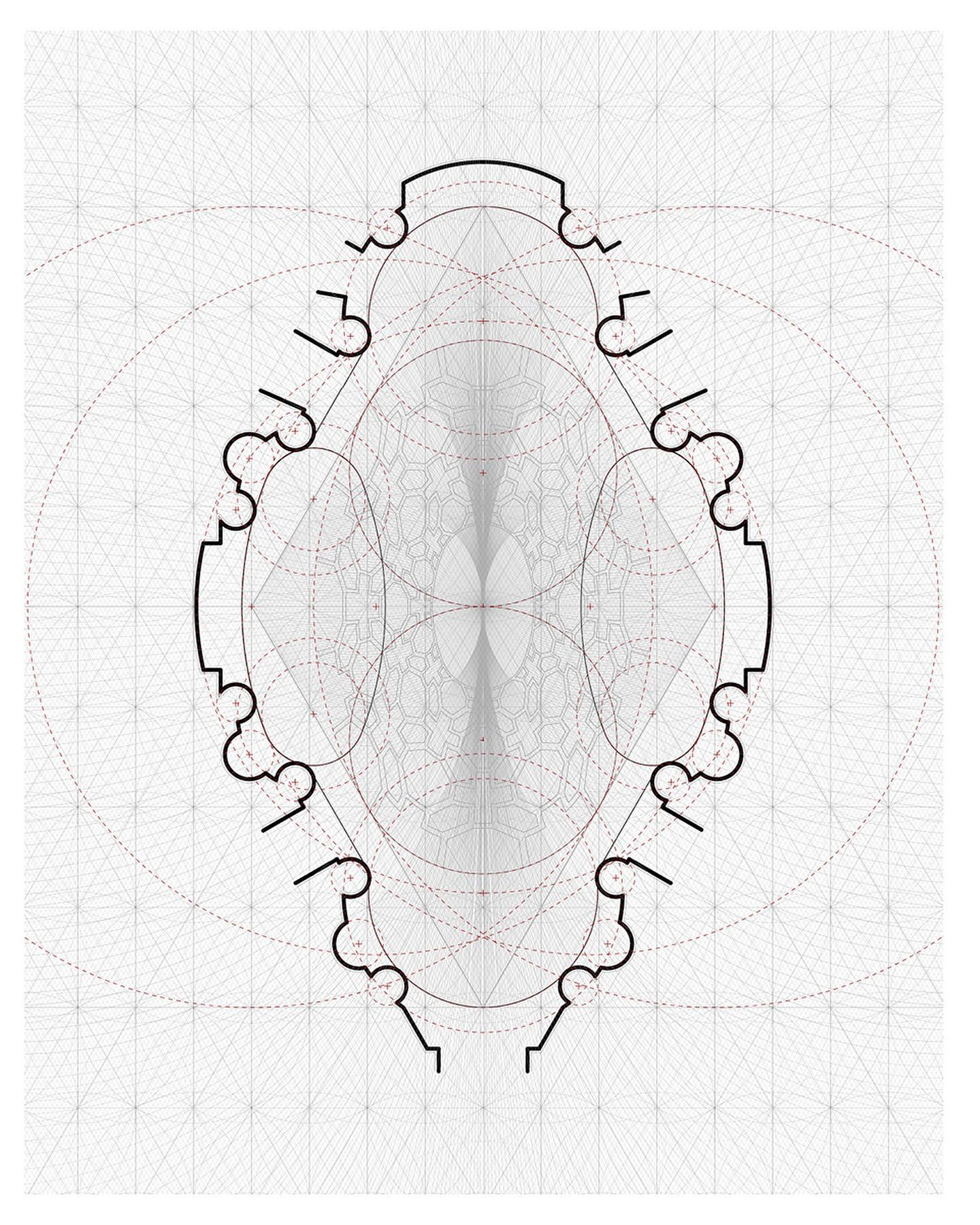

Circles are stretched to ovals. Parts are distort and inflect towards one another. In the Baroque the parts themselves compose a greater whole through inflection and distortion.

Take Borromini’s San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane. This Roman chapel resembles it’s Renaissance counterparts but it is stretched along it’s central axis.

More of my words on the Baroque can be found here:

As well as my discussion of the Borromini Chapel above:

The shift from the Renaissance to the Baroque marked a compositional shift from harmony to distortion. By distorting classical forms, architectural composition opened up to unimaginable complexity. Parts no longer stood alone, only to be united by hierarchy. Parts could now bleed together or inflect towards a common axis, implying an organization through the independent posture of parts.

More images are shared below:

Modern Composition

As was seen above, there were rich theories of composition and aesthetics throughout architecture's canon. But things changed in the early 20th century. It is difficult to describe the composition theory of Modern Architecture because composition almost didn't exist. The classical language of parts, wholes, or inflections seemed outdated to many modern architects. The arrangements of architectural elements were to be dictated by function instead of any formal or aesthetic principles. When the Renaissance and Baroque designers sought expression of form, modernists pursued abstraction. Architecture aspired to be neutral, efficient, and rigorously logical. Any formal expression was reserved for communication and function legibility.

The result was an architecture of formal efficiency.

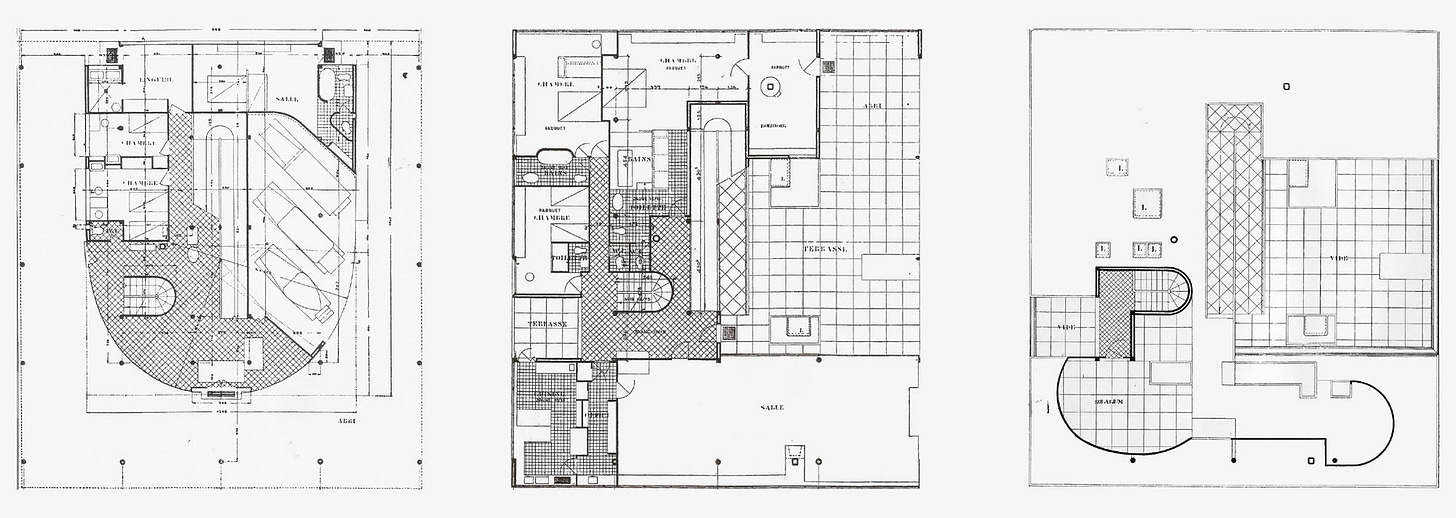

Even the architectural drawings reflected this change. Plan drawings which are used to communicate spatial organization used to display it’s poche with a thick black shading to communicate the figural qualities of form. In the Modern era, poche became a tool to communicate wall materials and construction.

Postmodern Return to Composition

“An architecture of complexity and accommodation does not forsake the whole. In fact, I have referred to a special obligation toward the whole because the whole is difficult to achieve. And I have emphasized the goal of unity rather than of simplification in an art ‘whose . . . truth [is] in its totality.’ It is the difficult unity through inclusion rather than the easy unity through exclusion.”

By the mid-20th century, the cracks in modernism's dogmatic logic had begun to show. Its rhetoric of exclusion and simplicity clashed with the specific, layered, and often contradictory realities of actual building programs and urban contexts.

In response to such a condition, Robert Venturi wrote Complexity and Contradiction, which reponed the conversation around the composition.

Venturi wasn't necessarily calling for a return to the Baroque or the Renaissance, but rather, a new kind of composition that could accommodate contemporary society's complexity.

Venturi lays out his theory most directly in the penultimate chapter of his book. It rejects the idea that the whole should be simple or clean. Instead, it calls for an architecture that accepts complexity and contradiction and composes them into a meaningful, but sometimes difficult, whole.

Venturi's central claim is relatively straightforward: the architect has an obligation toward the whole, even when that whole is difficult to achieve. In modernism, wholeness was often pursued through simplification. Mies van der Rohe avoided the complexity of buildings and thus made architecture abstract. Venturi, instead, insists that unity gained through exclusion is incorrect. The real task is to create unity through inclusion—of difference, contradiction, and parts that don't easily fit.

Venturi speaks of three main ideas that were suppressed during Modernity: duality, inflection, and superposition.

Below are quotes on all three, but I recommend reading the whole chapter, which can be found in this PDF.

On Duality:

“Our recent architecture has suppressed dualities. The loose composition of the whole used in the ‘binuclear plan’ employed by some architects right after the Second World War, was only a partial exception to this rule. But our tendency to distort the program and to subvert the composition in order to disguise the duality is refuted by a tradition of accepted dualities, more or less resolved, at all scales of building and planning—from Gothic portals and Renaissance windows to the Mannerist façades of the sixteenth century and Wren’s complex of pavilions at Greenwich Hospital.”

On Inflection:

“Inflection in architecture is the way in which the whole is implied by exploiting the nature of the individual parts, rather than their position or number. By inflecting toward something outside themselves, the parts contain their own linkage: inflected parts are more integral with the whole than are uninflected parts. Inflection is a means of distinguishing diverse parts while implying continuity. It involves the art of the fragment. The valid fragment is economical because it implies richness and meaning beyond itself.”

On Superposition

“A more difficult unity can also result from the superimposition of two or more diverse orders, sometimes spatially, sometimes in different aspects of the same element. The resulting duality can be confusing and ambiguous, or it can be tension-producing and dramatic.”

A few years after this book was published, it was already impacting the student work of various architecture programs in the US. The program most strongly affected by this was The Cooper Union. Below are some photos and a link to my words on the Pedagogy.

Venturi’s theory of the difficult whole is not purely about aesthetics and composition. It is the recognition that architecture reflects the layered, unresolved, and often contradictory realities of the world. Today, as architects confront cultural multiplicity, ecological urgency, and urban complexity, the difficult whole remains a sharp and generous alternative. It is an ethic that holds things together without flattening them. I hope that like me, you can find a great relevance in this philosophy.

Thank you for reading. If you enjoyed, please consider supporting <3

As a new reader of your publication in Substack, I have been enjoying your clear definitions of architectural styles---classic, baroque, brutalist, and postmodern.

Next, I hope that you will tackle the distinctions between arts & crafts, beaux arts, art nouveau. art deco. . . and modern. In social media deco is often confused with modernism, although early deco buildings have neoclassical plans and proportions. A style of modern, streamline, is referred to as deco on Wikipedia.

I am a graphic designer, not an architect, but my father was an architect, Joe Black. J. J. Black (1900-1982). A good student if never a graduate of Columbia Architecture, Joe was hired by Harvey Wiley Corbett as a part time draftsman in 1924. This led to project design work for Raymond Hood, who had worked in Corbett's office. Joe had a long association with Wallace K. Harrison, another Corbett alumnus, and continued as a freelancer, working with other luminaries, such as Joseph Urban, Ralph Walker, and Edward Durell Stone. In 1929, now a registered architect, he joined the firm of associates put together (by Corbett) to design Rockefeller Center.

Joe got experience on some great modern buildings, but most of the time he was designing parts of beaux arts structures, such as the facade of the Ziegfeld Theater for Urban.

For Stone, he worked on the exteriors of what he called "Theater 2, the RKO theater on the southwest corner of 6th Ave, designed as a bookend to match the Music Hall. Finishing up with tenant alteration plans at Rockefeller Center through 1932, he hit the Depression slump in new constructions. With my mother and oldest sister, he moved to Midland, Texas in 1934. After the war he built a successful practice, mostly residential.

As a Corbett student, he was well schooled in architectural history, and kept up with the enormous changes in his lifetime. (He could date any building within a year or two, just by looking at it). Late in his life I asked him if he was happy to see the postmodern movement happening, and new appreciation for the beaux arts, which had been condemned by the modernists as hopelessly eclectic.

"Oh, Roger, I was never a beaux arts architect. I like to think of myself as arts & crafts."

This was about building "natural" buildings with great materials and beautiful craftsmanship, he explained.

Joe had always talked about Bertram Goodhue, as arts & crafts, even though he did many neoclassical, gothic, and Spanish colonial revivals. Joe was delighted that I was going to spend a lot of time as a choirboy in one of Goodhue's greatest buildings, St. Thomas Church in New York. He had a second generation connection through Corbett and Harrison---both having worked in Goodhue's office.

He explained to me that arts & crafts (a style rejected by modernists as cute and bourgeois) was an alternative route to modernism, taken by Wright and Lutyens. Goodhue blazed that trail. From the beginning he had begun to simplify the forms. At St. Thomas I saw how he smoothed out the moldings in the gothic stone arches to leave a plain limestone wall.) And he was happy to use machines to do the heavy lifting. (Lee Lowry, his sculpture discovery, had a shop with 100 men using power tools.) Later, Goodhue produced essentially modern buildings: the LA library and Nebraska state capitol.

This note has gone on too long, but I am fascinated in the alternative arts & crafts route to modernism. Most of my father's houses were "natural" and easy-to-take, with a lot of carefully laid masonry and hand-carved wood. But the commercial buildings used steel, concrete, and glass. And they were modern.

_ _ _

Hope you can clear up the distinctions between these styles, as you have done for the others!

_______________________________________________________________________________

Five samples of my father's work"

https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1u4RYgRSWhyTkMWOkCRBK0nGeWUauXLfo?usp=sharing

Such a pretty writing. Thoroughly enjoyed 🥲