This Substack is by David Perrine. I write about architecture, aesthetics, design theory, and philosophy. I share new posts bi-weekly. If you enjoy my work, please consider subscribing.

I have recently started reading Deleuze in an attempt to understand his notion of “The Fold” and its significance in architectural theory. In doing so, I’ve realized how his work is often misrepresented and misread in architecture circles. This text is my attempt at making accessible Deleuze’s notion of the fold, how it has influenced architecture and how it gets misused. I will start with a brief introduction by outlining the relevance of Deleuze’s notion of ‘The Fold’ in architectural theory. Then, we will discuss his text directly, followed by a look into how he has been read and misread.

I hope you enjoy

Introduction

Deleuze develops his concept of the fold in his work “The Fold: Leibniz and the Baroque”. This book was first published in 1988 by Éditions de Minuit in French. The English translation by Tom Conley was published in 1993. Soon after, Greg Lynn edited an issue of “AD,” an architectural design magazine, entitled, “Folding in Architecture” in 1993. This issue generally sought to embed the ideas of Deleuze into a new architectural theory using the emerging digital technologies of the time, primarily, calculus-based three dimensional modeling tools. It included essays by Greg Lynn, Peter Eisenman, Jeffery Kipnis, Philip Johnson, Mario Carpo, Frank Gehry, and others. It also included the first chapter of Deleuze’s “The Fold: Leibniz and the Baroque”. “Folding in Architecture” would later be grappled with and cited by architects and theorists such as Zaha Hadid, Antoine Picon, Patrick Schumacher, Ignasi de Solà-Morales, and more. Deleuze’s text and its analysis remains influential to the field of architecture today largely because of the work of Greg Lynn and Jeffery Kipnis.

Before I get into my words on The Fold, I want to provide a brief disclaimer. This essay is very much an aggressive simplification that may upset those who are well versed in the minutia of Deleuze’s work. I want to be very clear that this text is an attempt to make accessible a very strange work of philosophy and some amount of accuracy, elegance, and meaning will be lost. There is no substitute for reading Deleuze’s own words.

On that note, I hope you find my words useful or at least entertaining.

Folds and Floors

The text opens with two main assertions. First, is that of the fold, and second is that of floors.

Deleuze’s Concept of the fold is first and foremost a metaphysical theory. That is, it suggests a holistic theory for how the world operates. Essentially, Deleuze suggests that the world and everything in it (time, space, ideas, matter) is composed of a single, continuous material. Things that appear to be discrete objects are simply given form and supposed discretion through a process of folding and curvature. Although this notion is supposedly metaphysical, I would recommend thinking of this idea metaphorically. The use of a ‘fold’ as the primary unit of matter is strange because folds are typically understood as a joint as opposed to a thing. This type of language is used to emphasize the ‘oneness’ of matter, of time, of everything. It should also be mentioned that the fold is conceptualized as a smooth curve as opposed to a sharp crease. He further expands on this idea by categorizing two types of folds: pleats of matter, and folds of the soul. In both cases, folds are generated through various types of forces which affect the drapery of matter.

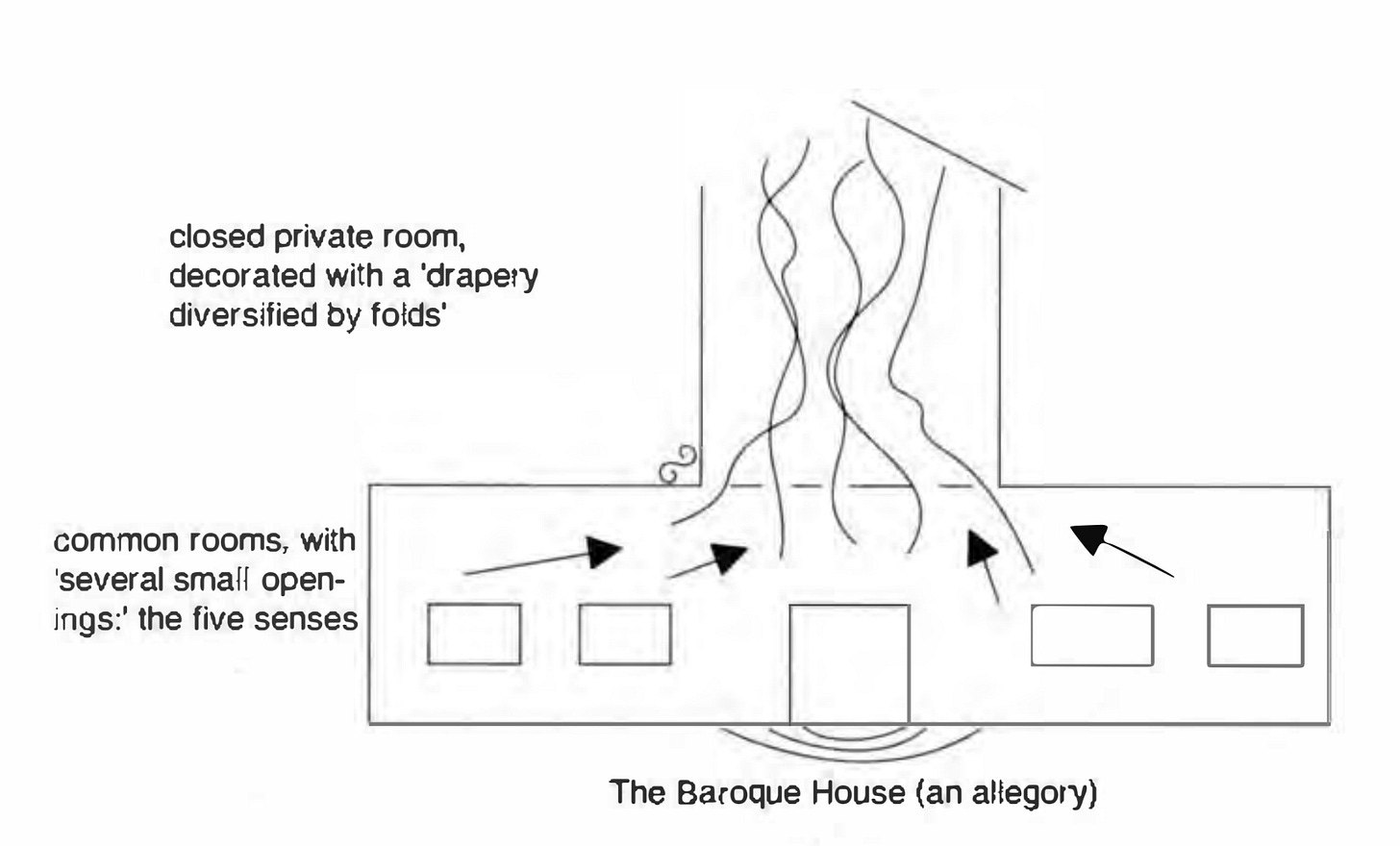

The differentiation between matter and the soul presents the introduction of his idea of floors. In his allegory, there is a house with two floors. This allegory can be thought of as a metaphor for a human individual with their corresponding transcendent dimension and physical dimension. The upper floor represents the the soul. The soul does not communicate with the physical world outside of the home. The upper floor has no windows or doors. The soul indirectly communicates with the outside world through ‘cords or drapery’ which folds as it connects the upper and lower floor. It is purely an interior with no direct relationship to an exterior. The lower floor represents an individual’s physical hardware. It is their body. It is pierced and opened selectively. The openings are the ways in which a human individual interacts with the exterior world.

To Deleuze, both of these rooms possess their own ‘infinities’. The upper room represents an infinity of meaning. It ‘sings to god’. There is a freedom and immateriality of the soul. It is elevated. The lower floor possess an infinity as well. To Deleuze, matter is made up of a fractalesque series of folds. Folds exist inside of folds continuing to the infinitesimally small.

Below is Deleuze’s text on the two floors:

“… the Baroque differentiates its folds in two ways, by moving along two infinities, as if infinity were composed of two stages or floors: the pleats of matter, and the folds in the soul. Below, matter is amassed according to a first type of fold, and then organized according to a second type, to the extent its part constitutes organs that are "differently folded and more or less developed." Above, the soul sings of the glory of God inasmuch as it follows its own folds, but without succeeding in entirely developing them, since "this communication stretches out indefinitely." A labyrinth is said, etymologically, to be multiple1 because it contains many folds. The multiple is not only what has many parts but also what is folded in many ways. A labyrinth corresponds exactly to each level: the continuous labyrinth in matter and its parts, the labyrinth of freedom in the soul and its predicates. If Descartes did not know how to get through the labyrinth, it was because he sought its secret of continuity in rectilinear tracks, and the secret of liberty in a rectitude of the soul. He knew the inclination of the soul as little as he did the curvature of matter. A "cryptographer" is needed, someone who can at once account for nature and decipher the soul, who can peer into the crannies of matter and read into the folds of the soul. Clearly the two levels are connected (this being why continuity rises up into the soul). There are souls down below, sensitive, animal; and there even exists a lower level in the souls. The pleats of matter surround and envelop them. When we learn that souls cannot be furnished with windows opening onto the outside, we must first, at the very least, include souls upstairs, reasonable ones, who have ascended to the other level ("elevation"). It is the upper floor that has no windows. It is a dark room or chamber decorated only with a stretched canvas "diversified by folds," as if it were a living dennis [sic]. Placed on the opaque canvas, these folds, cords, or springs represent an innate form of knowledge, but when solicited by matter they move into action. Matter triggers "vibrations or oscillations" at the lower extremity of the cords, through the intermediary of "some little openings" that exist on the lower level. Leibniz constructs a great Baroque montage that moves between the lower floor, pierced with windows, and the upper floor, blind and closed, but on the other hand resonating as if it were a musical salon translating the visible movements below into sounds up above” (Deleuze 4).

The Baroque

This combination of levels and folds builds the fundamentals of his metaphysics. To Deleuze, an expression and acknowledgement of said metaphysics is found in the Baroque. He argues that the Baroque represents a series of operations and a catalogue of attributes which actually transcends an epoch specific style. He opens with a line about how Baroque architecture is not an invention, but rather, a development on elements from previous styles:

“The Baroque refers not to an essence but rather to an operative function, to a trait. It endlessly produces folds. It does not invent things: there are all kinds of folds coming from the East, Greek, Roman, Romanesque, Gothic, Classical folds. . . . Yet the Baroque trait twists and turns its folds, pushing them to infinity, fold over fold, one upon the other” (Deleuze 3).

Later, Deleuze write a chapter specifically called “What is Baroque”. Here, he outlines a series of attributes which encompass the Baroque. These attributes both differentiate the Baroque from other styles and it also allows the Baroque to transcend its historical limits.2

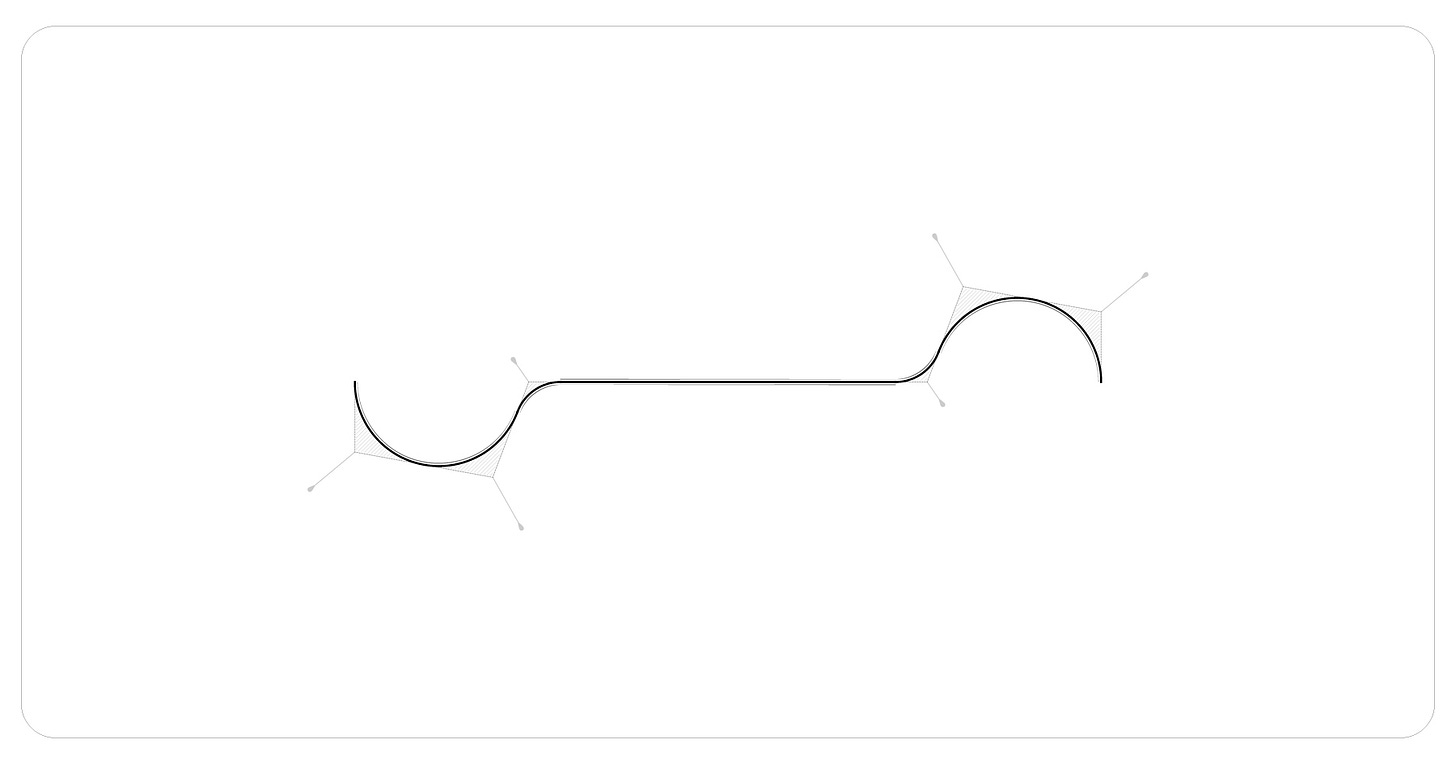

The Fold — For Deleuze, the fold exists whether it is formally expressed or not. The Baroque still express the fold through a continuity of form and ornamentation. I will remind the reader that formally, a fold is more so a curve which connects two two things via inflection point. It should not be understood as a sharp crease.

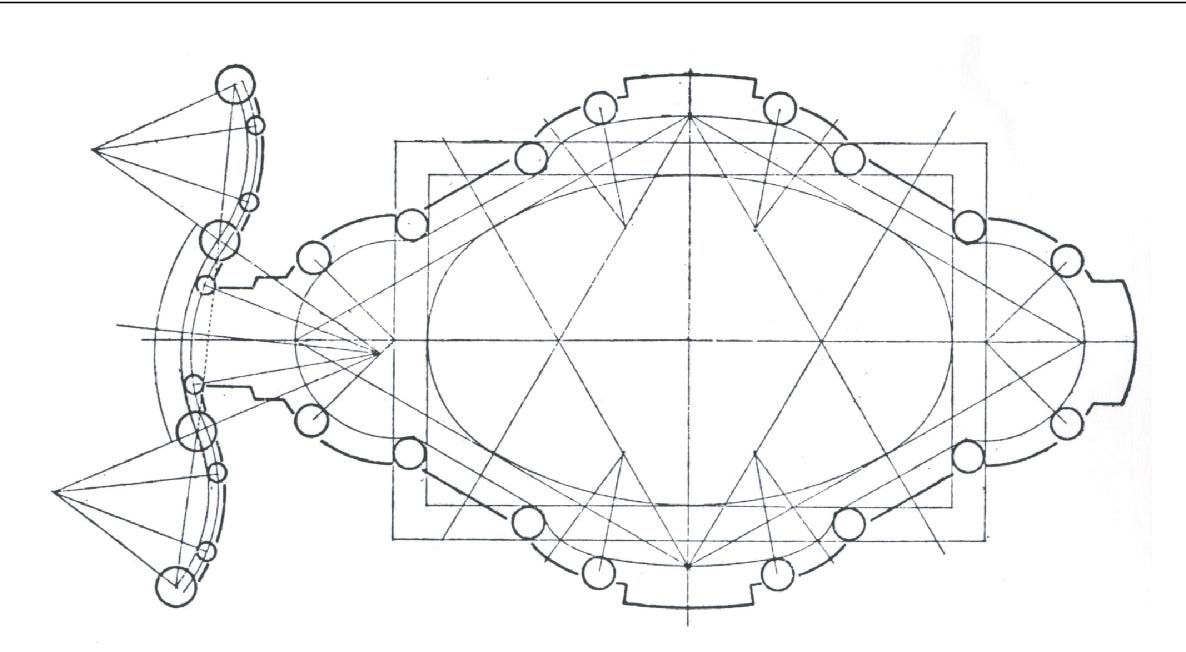

The inside and the outside // The high and the low — Deleuze discusses two levels in his allegory (an upper level which represents a pure interior and a lower which interacts with an exterior). These two levels are subtly connected while maintaining and privileging their discreetness. The Baroque possess a parallel dichotomy, that is, the interior chapel and it’s facade. These two entities although being elements of the same church, often are formally unrelated. They remain separate systems. I discuss this briefly in my analysis of Borromini’s San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane. In Baroque chapels, the interiors remain pure often without visible apertures. Most of the openings are hidden from view. This of course is a significant departure from the large stained glass windows of the Gothic.

The unfold — This attribute of the Baroque is related to continuity. Here, Deleuze posits that an unfold is not the contrary or negation of the fold, but rather a continuation. The aesthetic precedent used for this attribute are the paintings of Simon Hantai.

In his work, the white space contributes just as much to the painting as the colored figures. One should not think of the white space as a negative space. In the Baroque, the same is true. The ‘negative voids’ conceal themselves or masquerade as positive content.

Texture — Texture in objects is caused by two types of forces: active forces and passive forces. Active forces are those which directly deform a material causing ripples, craters, or dents (all of which are of course variations of folds). Passive forces are forces that are innate to the specific material, thought of as an interior resistance or physical property. These two forces and specific nature produces folds. Texture is not something that is separate from an object, but a part of it’s essence. In the Baroque, texture becomes an expressive system. It appears in the folds of drapery and pleated paper of letter holder paintings. Although the texture of an object remains vital to Deleuze, it should never obscure the formal essence of said object.

The paradigm — Here he claims that the Baroque encapsulates a certain paradigm. For example, their exists a Greek fold which various from the Baroque fold. The Greek fold is based in an exactness, repetition, proportion, and geometric clarity. Thus, it limits the potential of folding by controlling it. A true paradigm of the fold encourages variability and flexibility. The fold then becomes an expressive force through art and politics as opposed to a simple geometric means to a simple end. The fold is about dynamic expression and infinite variability and transformation.

On Readings and Misreadings

As you can see. The fold presents a metaphysical construction which stresses continuity, forces, and the divine. It is not that Deleuze is arguing for architecture to appear to be made of actual folds. Instead readers should look to understand the various forces that affect architectural projects and to engage with them. Many architects have chosen to follow this doctrine. For example, In “Arguing for Elegance”, Patrik Schumacher writes:

Elegance requires that the layers and subsystems of a complex composition are mutually inflected. Every new element or new layer that enters the complex will both inflect the overall composition and will in turn be inflected.

Elegance can never result from a merely additive complication.…

Elegant compositions or complexes are highly integrated formal/spatial systems that look like those highly integrated natural systems where all forms are the result of the lawful interaction of physical forces or like organic system where the forms result from a similar play of forces selected and integrated in adaptation to performance requirements. Such elegant compositions resist decomposition, just like their natural models.

A specific aspect of this overall lawful and integrated nature of elegance is the capacity of elegant compositions to adapt to complex urban contexts. Adaptive capacity or adaptation is another key ambition of the contemporary avant-garde trend that might suggest comparison with natural organic systems. An architectural system that has an enhanced capacity to adapt to its environment will result in an intricate artifact-context ensemble that has sublated initial contradictions into a new complex synthesis that further enhances the overall sense of sophisticated elegance.

We can see the influence of Deleuze. Schumacher stress positive sentiment with systems that respond to forces and rely on inflection between elements. (Deleuze at times equates inflections and folds).

On the contrary, other architects such as Antoine Picon occasionally make a case for the expression of the opposite. In “Intricate or Minimalist Elegance”, Picon writes:

In a similar vein, one may wonder whether one of the roles of architecture still awaiting reinvention in the digital age does not lie in a protection from too much exposure to the invisible flows of information that structure our lives. One cannot but be struck by the strange peace that reigns when wireless signals disappear, when cell phones and computers no longer chain us to mundane tasks and concerns. What if one of the possible roles of architecture was actually to protect us from the hustle and bustle of the digital world instead of mimicking its agitation? A different kind of elegance could then become possible, an elegance based on discretion rather than overstatement, on minimalism rather than mannerist or baroque-like intricacy. The new requirements linked to the pursuit of sustainability are also pushing in that direction.

I hope you found this useful. Please feel free to leave a comment if you have any questions or thoughts.

Thank you for reading. Please consider subscribing.

In the original French publication. The word word ‘multiple’ can also be translated as “manifold”. It is important because manifold means both a 'multiplicity, but has relevance in mathematics and topology. Find more here.

I would like to note that the idea of styles transcending their epoch was also applied to modernism within the decade of Deleuze’s Text by Sanjay Subrahmanyam who argued that modernization is more so an operative function as opposed to a specific event in the Western canon. “modernity is historically a global and conjuntual phenomenon, not a virus that spreads from one place to another. It is located in a series of historical processes that brought hitherto relatively isolated societies into contact, and we must seek its roots in a set of diverse phenomena - the Mongol dream of world conquest, European voyages of exploration… the “globalization of microbes”

Subrahmanyam, Sanjay. "Hearing Voices: Vignettes of Early Modernity in South Asia,

1400-1750." Daedalus 127, no. 3 (1998): 99-100.