In graduate school, a professor of mine assigned me to read excerpts from Georges Bataille’s “The Accursed Share”. The text puts forward an unconventional theory of economics based on surplus as opposed to scarcity of capital. Bataille argues that our society, over time, generates a buildup of excess potential energy, which is inevitably released through luxuries, artistic, or violent expenditures.

I found the text provocative, but I was still irked by my professor’s choice to assign this reading. Although I thoroughly enjoyed exploring these theories in my mind, I was confused about why I was reading them for a required architecture studio in a professional degree program.

Professor Klein would later clarify this choice with a claim I continue to hold dear today: Designers must equip themselves with the ability to justify ambitions and difficult or seemingly unnecessary design work.

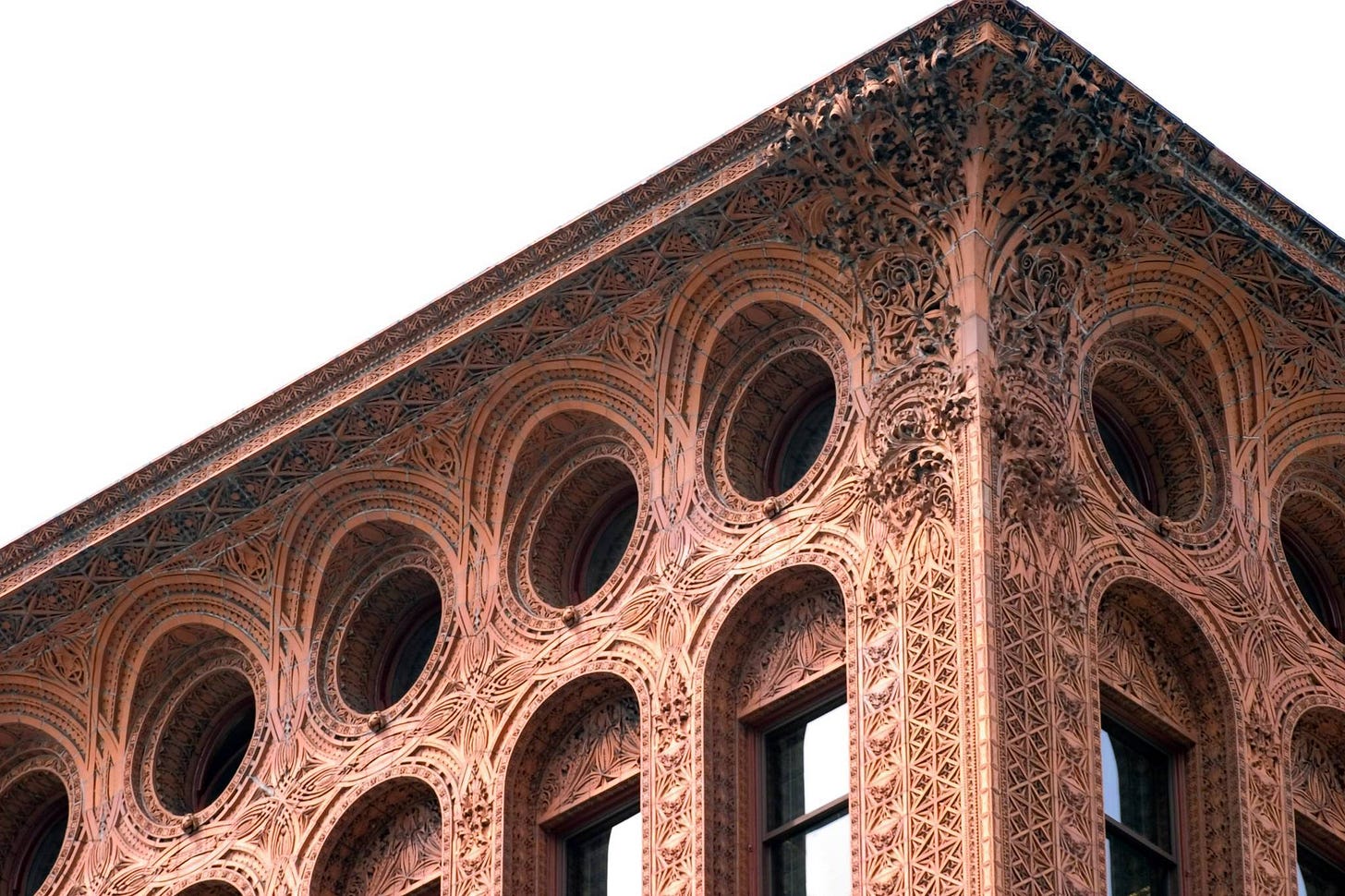

This line of thinking led me to think about ornamentation.

Ornament is a tough word to define in architecture. Most people understand the term as constructed elements that serve an aesthetic or symbolic function. This definition is too vague for architectural application because many elements hold aesthetic value while serving a non-aesthetic function. Are objects which possess both functional and aesthetic value ornament? What if an object is functional but painted to provide a visual contrast to other elements? Is said element suddenly ornamental? At what point is an object too functional to be considered ornament?

The Alamillo Bridge presents a wonderful thought experiment on the matter. On one hand, the bridge does not appear to possess any ornamental elements. The cables are necessary for structure, and so is its lone slanted column. However, the river's span would have been better served by a conventional suspension bridge. Such structure would have been far more structurally and materially efficient, simpler to build, and cheaper. Calatrava chose this form for its aesthetic quality. Does this make these structural elements suddenly ornament? Is the bridge itself a small ornament at the scale of the city? To me, this question is by no means simple, and digging into interpretations of the word “ornament” is beneficial.

I am generally against citing dictionary definitions of words. But in this case, it further unravels the concept as opposed to clarifying it. Thus, I am willing to share.

According to the Cambridge Dictionary, ornament is “An object that is beautiful rather than useful.”1 They also comment that ornaments are usually small, and thus, elements that define or organize compositions do not qualify.

Merriam-Webster defines the term in a few different ways, first as “something that lends grace, beauty, or festivity.”2 They also list its archaic definition as “a useful accessory.” In music, the term can refer to “an embellishing note not belonging to the essential harmony or melody.”

Some definitions mention ornaments’ potential for function, while others say a use value rules out an object as a piece of ornament.

The musical definition is fascinating. It calls ornament an unnecessary embellishment. Something that a musical piece can stand without. If something being removed from a composition fundamentally changes the composition, then the thing being removed is not ornament.

This definition doesn't apply well to architecture because it is simultaneously too specific and complex. For example, the effect of the Wallfahrtskirche Basilika Birnau is produced by an aggregation of small ornamental parts that inflect towards a whole. If any individual part is removed, the composition has not fundamentally changed, just as sentences are still readable if a single lettr is removed. In this case, each piece fits the definition of an ornament. However, an elimination of every piece destroys the composition, as the collection of individual inflections of each part generates the composition. Each piece of ornament is simultaneously expendable yet necessary.

The most useful definition of ornamentation in architecture I have seen was formulated in Farshid Moussavi’s The Function of Ornament, published in 2007. Moussavi understood the importance of specificity, which is evident in her choice to differentiate the term from décor.

To Moussavi, ornamentation is simply a form that produces an effect. It is inseparable from an object. No object, no matter how austere, is without an ornamental quality. It comes from a material’s chemistry, context, construction, shape, and even growth. This differs from décor, which is directly representational and doesn’t affect all forms. Décor is directly symbolic. Ornament is abstract. Moussavi does not attempt to separate ornamentation from function.

Moussavi’s words:

“Ornament is the figure that emerges from the material substrate, the expression of embedded forces through processes of construction, assembly and growth. It is through ornament that material transmits affects. Ornament is therefore necessary and inseparable from the object. It is not a mask determined a priori to create specific meanings [as in Postmodernism], even though it does contribute to contingent or involuntary signification [a characteristic of all forms]. It has no intention to decorate, and there is in it no hidden meaning. At the best of times, ornament becomes an ‘empty sign’ capable of generating an unlimited number of resonances.

Whereas décor and representation promoted by Postmodernism correspond to a self-limiting movement from the possible to the real which cannot create anything new, ornament is in line with non-representational thought and the creative actualization of the virtual. Decoration is contingent and produces ‘communication’ and resemblance. Ornament is necessary and produces affects and resonance.” (Moussavi, 8)

This definition is particularly useful because it allows us to discuss ornamentation during architectural epochs in which ornamentation was supposedly dead.

Historically, the 20th century is often regarded as the end of ornamentation in architecture. This death started with the denouncing of ornament as a mechanism for architectural communication and ended with the complete elimination of ornamentation from architectural discourse. Ornamentation (décor) was ‘revived’ in 1972 by Denise Scott Brown and her husband, Robert Venturi.

This moment, sparked by the aforementioned authors in the 70s, was revelatory. We were now supposedly free from the dogmatic austerity of Modernity. In reality, the majority of the field still rejected Brown and Venturi’s contributions and continues to do so. Only a few practices have integrated their ideas and have developed upon them. Thus, this story of a revolution is generally overstated. Just speak to an American university professor about these two. You are likely to hear a particular set of objections such as “they are interesting but impractical” or “their theories work better as experiments.”3

Furthermore, this revival wasn’t simply a theoretical justification for the return to ornamentation/décor as we once knew it. Two main arguments were being made on this front. First, they argued for a new style of formal communication that could be married to the Modern Architecture of the previous few decades. This concept was first articulated in their book Learning From Las Vegas (1972) and primarily advocates for the reintroduction of décor into contemporary architecture.

Essentially, they argued that using symbolism through a cladded décor could be a tool of architectural expression. To Scott Brown, décor didn’t need to relate to a building’s structure or program. Décor was a form of signage that acted independently of a building’s other functions.

If Learning From Las Vegas was an argument for décor, “Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture” was an argument for a new language of Moussavian Ornamentation. Pre-1966, ornamentation was still a part of architecture, but people weren’t really discussing it. Modern architecture (1929-66) was theoretically interested in material, construction, and structural simplicity. The Moussavian ornamentation of the time followed suit, appearing brutal and rigorously logical.4

Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture argued that a more complex epoch requires a more complex architecture and that we shouldn’t be worried about this expression. Venturi spends the text outlining the ornamental effects of this new complex architecture.

The lesson’s of Complexity and Contradiction are best demonstrated in the student work of Cooper Union during the 1970s as seen in this text. I wrote a bit about this student work here:

Also, some notes on Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture:

The implied argument by Moussavi is what I value most from her text. This argument runs contrary to the conventional understandings of ornamentation and décor. Conventionally, ornament and décor are dead. We don’t discuss the grammar of form and aesthetics because we have no reason to. Architecture needs to solve problems.

This argument misses Moussavi’s implicit claim. Whether intentionally or not, all objects have ornamentation value. It is “necessary and inseparable from the object.” It emerges from materials regardless of intent, and it will be poor in quality if not considered. A neglect of the ornamental conversation doesn’t eliminate it. It simply kills our ability to produce good ornament. It is here whether we want it to be or not. Moussavi would argue that today’s architecture doesn’t lack ornament, but that it lacks good ornament.

Therefore, we must consider the aesthetic qualities of our architectural interventions. Our structures will make aesthetic and cultural arguments whether we want them to or not. It would be irresponsible of us not to consider what our buildings are saying.

I hope you enjoy this piece on ornamentation.

Thanks,

– David

Thank you for reading, please consider upgrading to a paid subscriber to support my work.

https://dictionary.cambridge.org/us/dictionary/english/ornament

https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/ornament

Some programs are are mostly free from such objections such as Penn or Sci_ARC. In my experience, these schools are exceptions as opposed to the rule.

I just want to note how strange I feel describing the ornamental qualities of modernist architecture. I have been educated to beleieve that Modern Architecture by definition rejects ornamentation, but this is not the ornamentation that Moussavi is referring to.

Very good article, very necessary. Bringing back ‘details’ as part of function and design as one thing is part of our way back to a holistic experience of life. The amazing Louis Sullivan detail looks like it grew on or up with the building and makes it very sensual and changes the proportional relationship dramatically to bring people and the building closer together, like when one is in nature.

The word cosmos can mean ornament. And ornament comes from order, which is linked in PIE to ars - to join, as in art.

cosmos(n.)

c. 1200, "the universe, the world" (but not popular until 1848, when it was taken as the English equivalent to Humboldt's Kosmos in translations from German), from Latinized form of Greek kosmos "order, good order, orderly arrangement," a word with several main senses rooted in those notions: The verb kosmein meant generally "to dispose, prepare," but especially "to order and arrange (troops for battle), to set (an army) in array;" also "to establish (a government or regime);" "to deck, adorn, equip, dress" (especially of women). Thus kosmos had an important secondary sense of "ornaments of a woman's dress, decoration" (compare kosmokomes "dressing the hair," and cosmetic) as well as "the universe, the world."

https://www.etymonline.com/word/cosmos

ornament(n.)

c. 1200, ournement, "an accessory; something that serves primarily for use but also may serve as adornment; ornamental apparel, jewels," from Old French ornement "ornament, decoration," and directly from Latin ornamentum "apparatus, equipment, trappings; embellishment, decoration, trinket," from ornare "to equip, adorn," from stem of ordo "row, rank, series, arrangement" (see order (n.)).

The sense shift in English to "something employed simply to adorn or decorate, something added as an embellishment, whatever lends grace or beauty to that to which it is added or belongs" is by late 14c. (this also was a secondary sense in classical Latin). Meaning "outward appearance, mere display" is from 1590s. The figurative use is from 1550s; the meaning "one who adds luster to one's sphere or surroundings" is from 1570s.

ornament(v.)

"to adorn, deck, embellish," 1720, from ornament (n.). Middle English used ournen (late 14c.) in this sense, from Old French orner, from Latin ornare.

order(n.)

c. 1200, "body of persons living under a religious discipline," from Old French ordre "position, estate; rule, regulation; religious order" (11c.), from earlier ordene, from Latin ordinem (nominative ordo) "row, line, rank; series, pattern, arrangement, routine," originally "a row of threads in a loom," from Proto-Italic *ordn- "row, order" (source also of ordiri "to begin to weave;" compare primordial), which is of uncertain origin. Watkins suggests it is a variant of PIE root *ar- "to fit together," and De Vaan finds this "semantically attractive."

The original English word reflects a medieval notion: "a system of parts subject to certain uniform, established ranks or proportions," and was used of everything from architecture to angels.

https://www.etymonline.com/word/ornament

This is so interesting. I never thought of ornament as intrinsic to the object, it makes sense. I ask myself "where did ornaments go in architecture" from time to time while walking around Montreal.