Speculative Architectural Image 002 - Efficiency and Aesthetics in Architecture

A Cabin for Respite

This Substack is by David Perrine. I write about architecture, aesthetics, design theory, and philosophy. I share new posts weekly. If you enjoy my work, please consider subscribing.

This is the second piece in my series “Speculative Architectural Image” in which I discuss some of my own design work, the motivation and theory behind them, process of production, as well as other thoughts. Please Enjoy :)

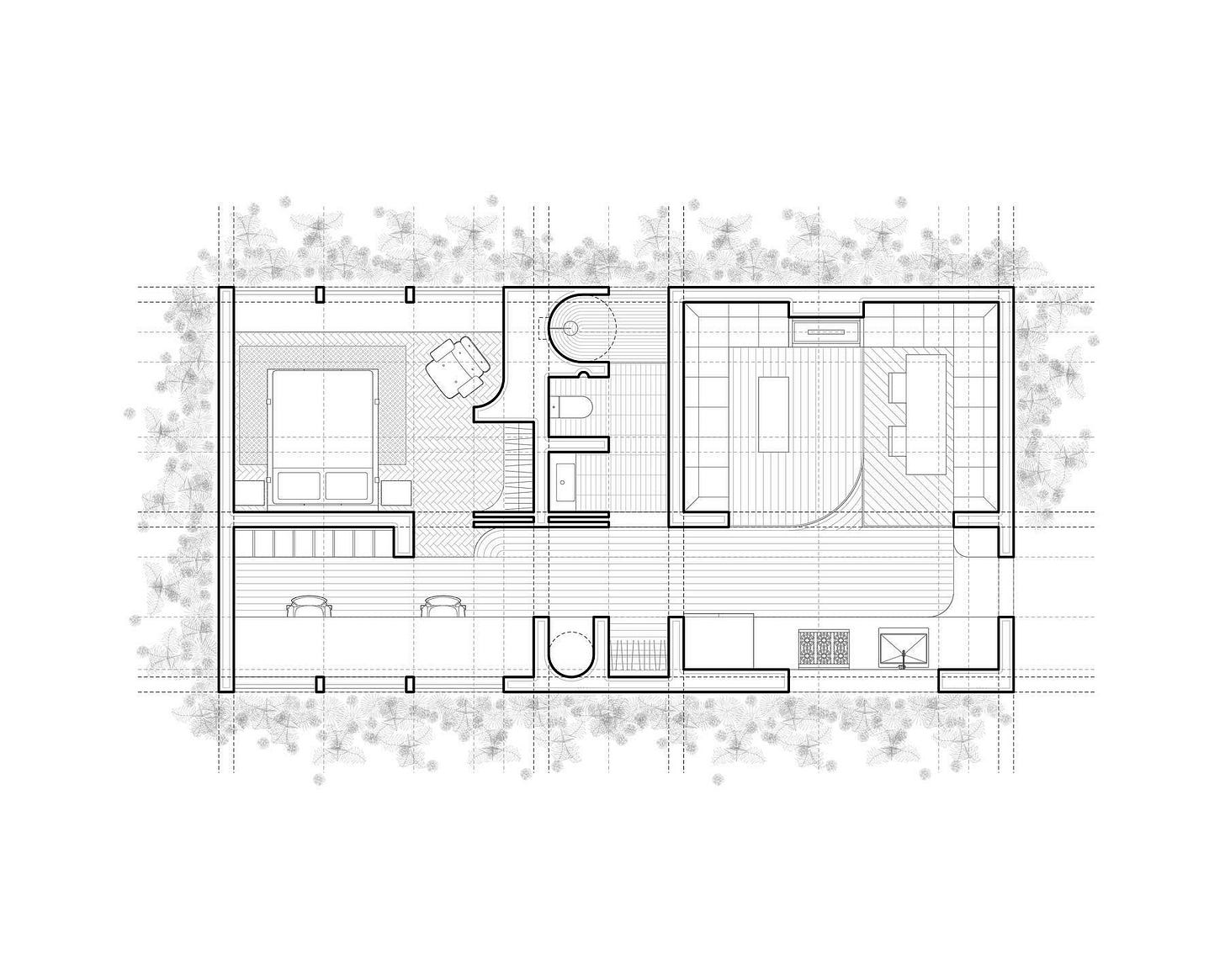

Above is a floorplan drawing of a cabin for two people. The cabin is approximately 660 sqft or 61 m2 and it includes one single-line kitchen, office space, bedroom which accommodates a queen sized bed, bathroom with a standing shower, living room with an alcohol burning fireplace, and dining space. 38 feet of its 112 feet perimeter is made of up glass. I drew this plan over the span of 2 weeks using a software called Rhino 7. I used Adobe Illustrator to adjust the line thickness and legibility.

My goal in the design was to reject complexity. Throughout my time in graduate school, I was encouraged to engage with complexity in my work—today’s cultural and political climate are strange and overwhelming; a complex and sometimes contradictory architecture is needed to contend with such reality.1 As a result, my work was strange, elegant, and polarizing (or at least it tried to be). It is the kind of architecture that looks interesting in a portfolio, but I doubt the average viewer would want to occupy my spatial interventions (See for yourself).

For the most part, my professor’s had successfully convinced me of this axiom. I agreed with the notion that a complex epoch requires a complex architecture, but I didn’t yet realize that this sentiment was only half of an important conceptual framework. The back half of this theoretical coin reaches an equally logical yet antithetical conclusion: That in complex times, an architecture of clarity and simplicity can provide a valuable respite to it’s users. In a sense, the role of architecture is not to mirror our culture, but to respond in a more adversarial way. More on this can be read here:

Along with simplicity and clarity, efficiency was also a design goal. Efficiency in architecture is a relatively simple criterion to evaluate. One simply needs to ask, what percentage of the buildings floor area is not useful. Efficient spaces will even accommodate multiple functions. Spaces that are efficient will have few hallways if any, as hallways cost money and they don’t serve much of a purpose. The hallways that do exist in efficient buildings will often serve other functions. Efficiency is important in architecture because efficient design is necessarily more economical and therefore, more likely to be built.

I posted this plan drawing on my Instagram account and it is by far my best performing post, a fact that I have quietly lamented. This success pointed to a disturbing suspicion I’ve had about my field: That most people judge images of our work based on it’s perceived efficiency, in other words, it’s ability to save money. The public judgement of our field has been plagued by the integration of the concept of beauty within efficiency. This is the definition of beauty in architecture now. Beauty has nothing to do with intricacy or composition, but rather, a space is beautiful if all your rooms fit neatly next to each other, if there are no dead corners, if the user has a place to put my shoes when I enter the space from the outdoors. Don’t get confused, readers. I understand that these questions are invaluable to the success of an architectural project, but this should not be the cause for calling a space ‘beautiful’.

Kant’s “Critique of the Power of Judgment” expertly differentiates these different notions of pleasure one can derive from an image or object. The words he used for these different pleasures were: agreeable, good, and beautiful. Essentially, An object is agreeable when it responds to a persons individual taste which is not influenced by the users ethical thoughts of the objects existence or an intersubjective notion of beauty. Someone enjoying a certain shade of green would find that particularly shade agreeable because we understand that enjoying colors is very much a personal judgement of taste. The adjective “good” is used to describe objects that agree with your sense of ethics or values. In other words, does that object have a right to exist. For example, I may find tiger fish the be aesthetically agreeable, but they are not ‘good’ because they are an invasive species in many parts of the world. Lastly, something is beautiful, if it appeals to ones sense of composition and proportion. It has a certain flavor of intersubjectivity in that one can’t image people disliking beautiful objects due to random personal preference. If someone dislikes my favorite color I understand that this is their preference and I would be wrong to be offended. This is different from someone thinking my belief that the Pantheon is beautiful is wrong (My favorite color is merely agreeable to me, but calling the Pantheon ugly feels akin to a crime).

In architecture, ones enjoyment of efficiency is more so a value judgement than an aesthetic one. Your enjoyment of efficiency is telegraphing your values of functionality, and your distain for wasting floor area, but this judgement has nothing to do with proportion, composition, or figure. Thus, it is not an aesthetic judgement but rather, and value based one.

To reiterate, I am frustrated that most people call an architectural intervention beautiful when it is merely efficient and functional. There is more to design than how it directly serves your greedy and uncultured appetite for program and 90-degree angles.

This cabin drawing is not beautiful, it depicts a space that is functional, spatially clever, and cost efficient. All useful things for a cabin to be, but none of these are a marker of beauty.

Thank you for reading. Please consider subscribing.

This opinion was held by most of my faculty. This take is also a ghost of Robert Venturi’s primary thesis in his 1966 text “Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture”