This Substack is by David Perrine. I write about architecture, aesthetics, design theory, and philosophy. I share new posts weekly. If you enjoy my work, please consider subscribing.

Last week, I was fortunate to give a small talk to a group of undergraduate students at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. The purpose of the lecture was to introduce a cohort first year students to the history of space-making and it’s effects on the development of floorplan drawings. I wrote this short article in preparation for that lecture.

In the research for the lecture. I came across two profound concepts in architecture, one about spatial conceptualization, and the other about the techniques of plan drawings. I was deeply interested in the relationship between these concepts which will be discussed the back half of this post.

Enjoy.

On Space

Today’s architectural landscape is chaotic. Contemporary architects produce an incredibly wide range of products and to some, it feels impossible to identify what our profession is holistically about. Some of us produce massive urban developments, others, small interiors or objects. We call ourselves researchers, artists, engineers, philosophers, designers, builders, or cultural critics. Despite this, I still observe a unifying truth which continues to loosely hold our profession together: Architects necessarily engage with space and its occupation.

According to architectural historian Sigfried Giedion, there exists a history of how architectural space was conceptualized and that each innovation in this history was spurred by the development of building technology.1 Specifically, Giedion noticed three distinct conceptualizations of architectural space:

Architecture as space radiating volume

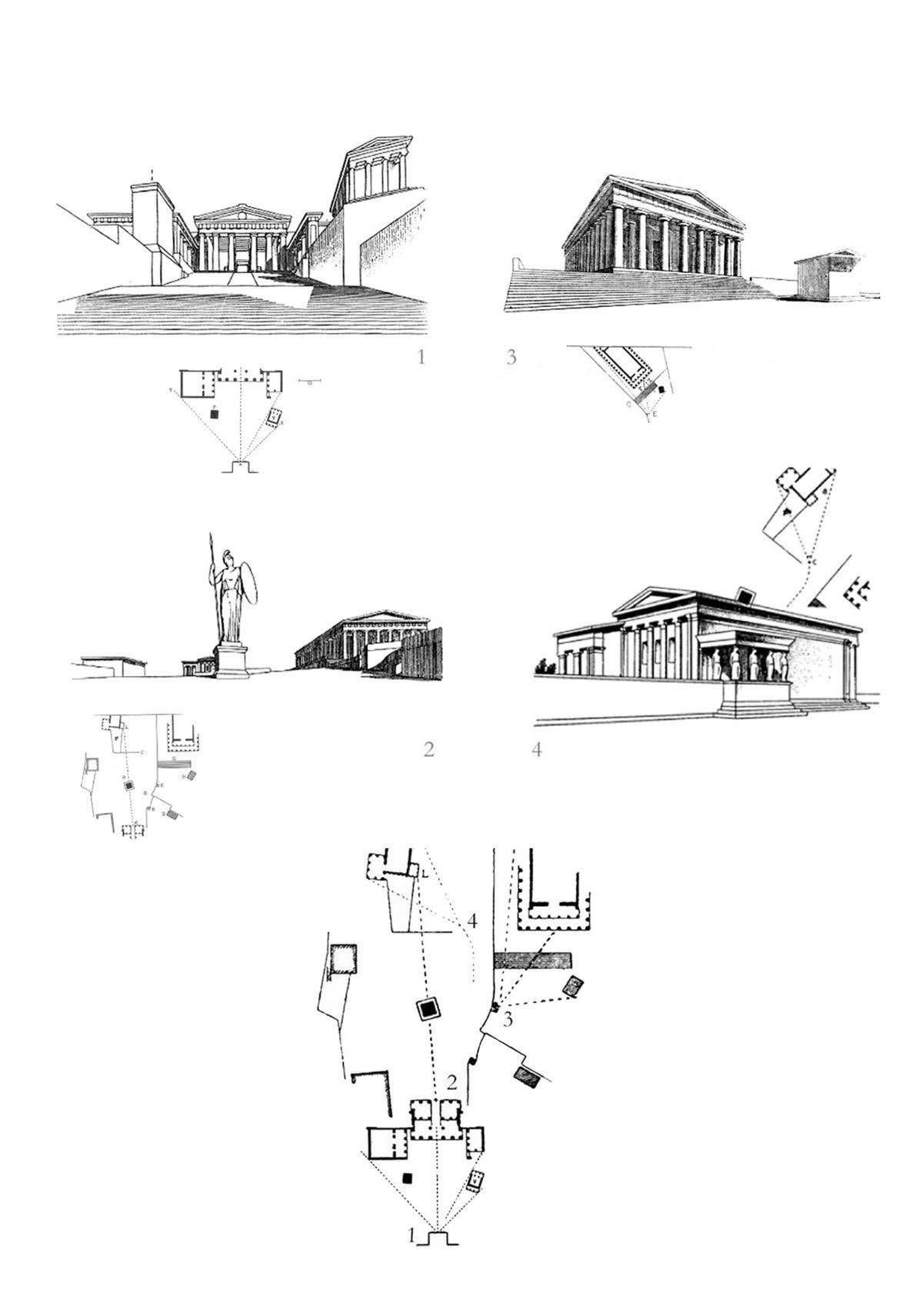

The space radiating volume was the first articulated conceptualizing observed by Giedion and it was the dominant conceptualization of architectural space in the first high civilizations: Mesopotamia and Egypt, and it persisted through Ancient Greece until the Roman Empire. Essentially, spatial generation was carried out by building objects that people could congregate around. This can be observed through the design of the Acropolis.

The Acropolis was designed as a composition of space radiating volumes. The interiority of each structure in the Acropolis was subjugated to the structures exterior affect. The planners thought more about how the temples look from the outside than the experience of their interiors. The temples thus possess a radiating affect. The diagram and site plan above show the careful placement of the temples and how they were composed to be observed from the acropolis grounds.

Architecture as interior space

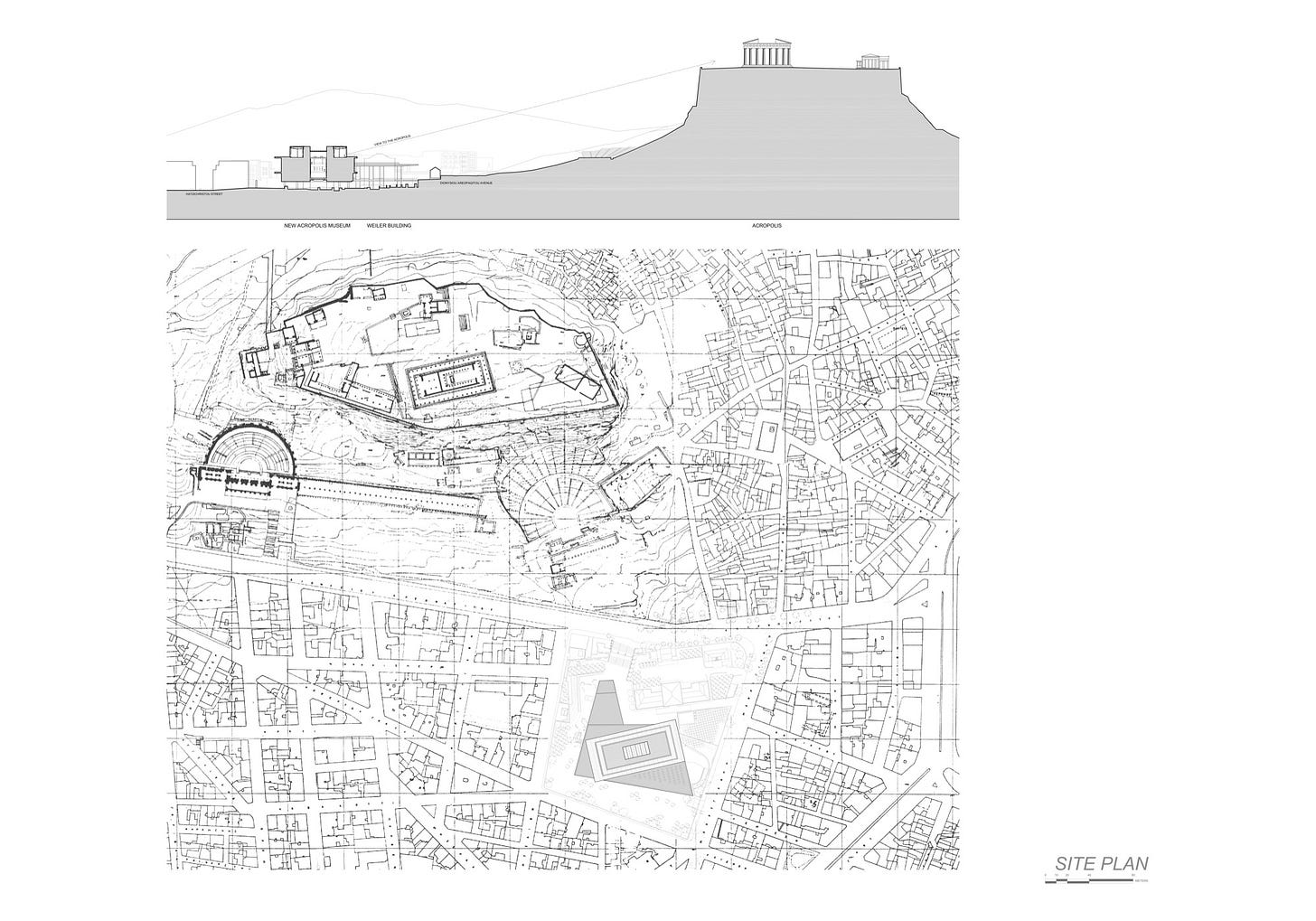

Giedion’s second spatial concept was called “Architecture as interior space.” The Roman’s innovated on the previous spatial conception by choosing to focus on architecture as a cavernous interior space. This was possible due to invention of concrete and other structural innovations. Nonetheless, it allowed the creation of spaces such as this:

These types of vaults were not buildable before the invention of concrete. Please notice the complex poche geometry.

Architecture as volume and interior space

Post industrial revolution, humankind developed the technology to produce architecture which not only radiated space around it, but also possessed potent interior spatiality. My favorite examples of this are the two buildings shown below, which both happen to be performance spaces.

On Plan

Floorplan drawings are elegant expressions of a spaces use, form, and aesthetics. In the same way that a mathematics formula may be appealing due to its ingenuity, clarity, or emergent properties2, plan drawings can be appealing in the same way. Thus, one should not think about floorplans simply as instructions for construction, but the expression of a spatial idea.

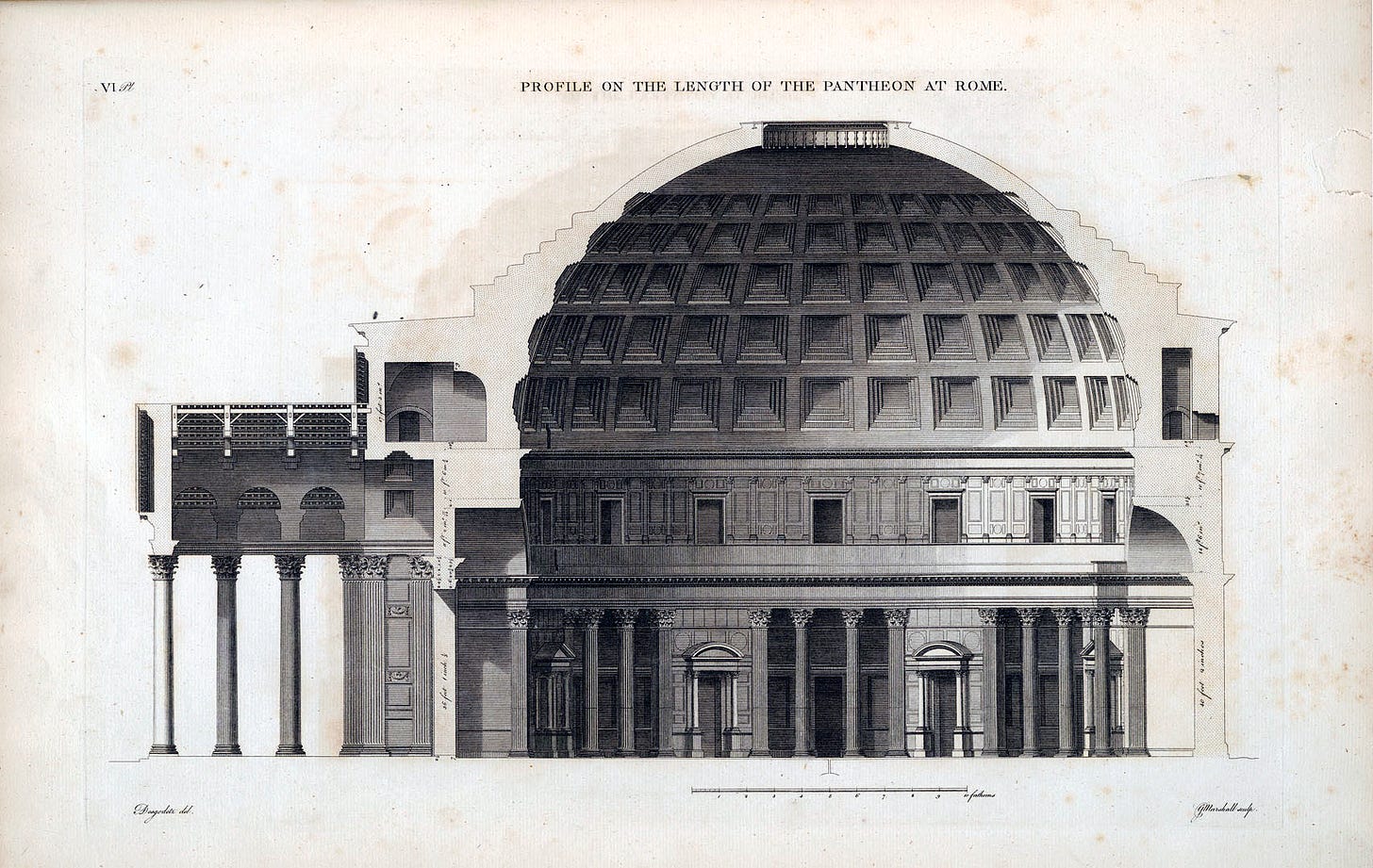

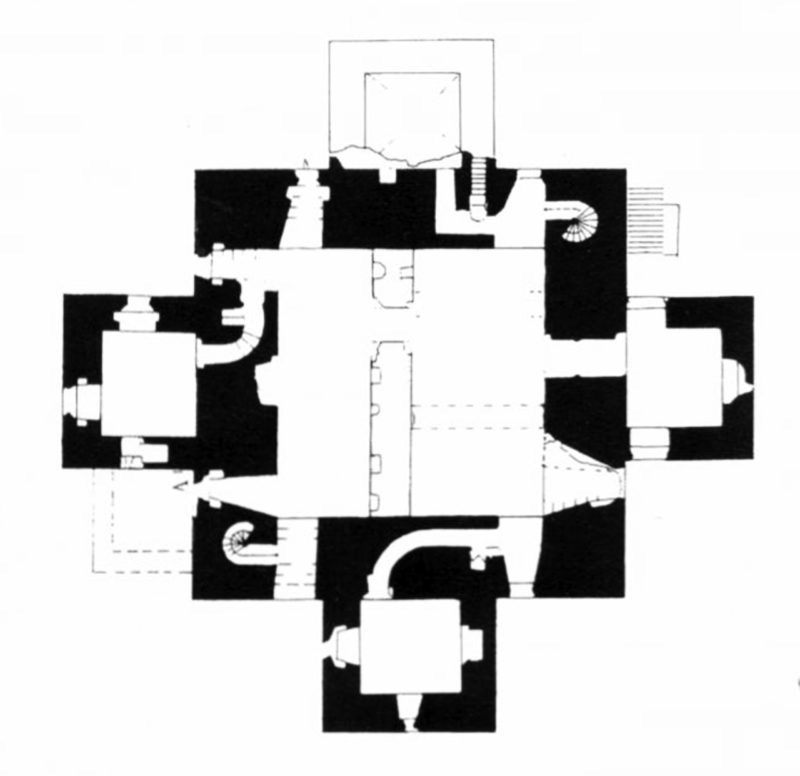

Michael Young’s “Reality Modeled After Images” lays out three techniques used in architectural plan drawings to communicate such spatial ideas. These are poche, entourage, and mosaic. Simply, poche refers to the representation of what is cut through in plan drawings such as walls, and columns, entourage refers to the people and objects placed in the drawing to communicate how a space ought to be used, and mosaic which is the graphical rendering of surfaces. Architects use these techniques to communicate their work. One can observe a drawing and understand the designers priorities based on which of these techniques were developed,

This drawing of a British castle shows a focus on the development of poche as a design tool. This focus on poche occurred because the construction of such towers was only possible with think masonry walls that were carved away to produce rooms, corridors, or stairwells.

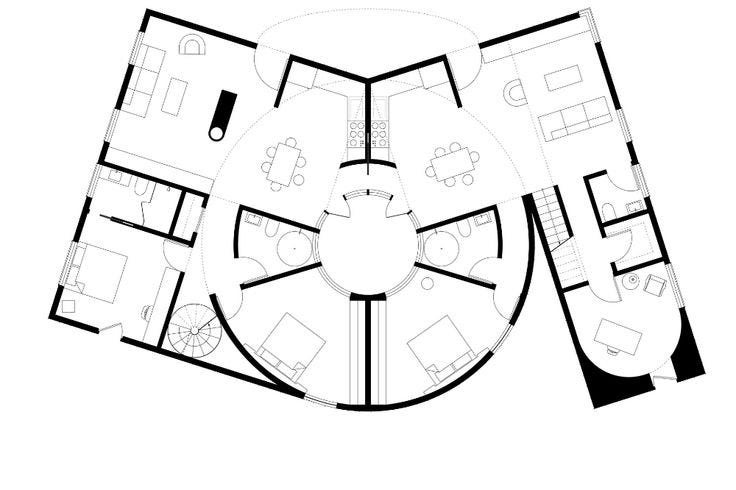

The Janus House was designed by Canty and focused almost exclusively on entourage. The beauty of this house is in it’s programmatic ingenuity, simplicity, and formal relationships. Thus, entourage is used to communicate spatial use. Canty generally avoids mosaics in his drawings. I would guess it reflects the idea that such aesthetic decoration distracts from what is important, spatial use, and formal relationships.

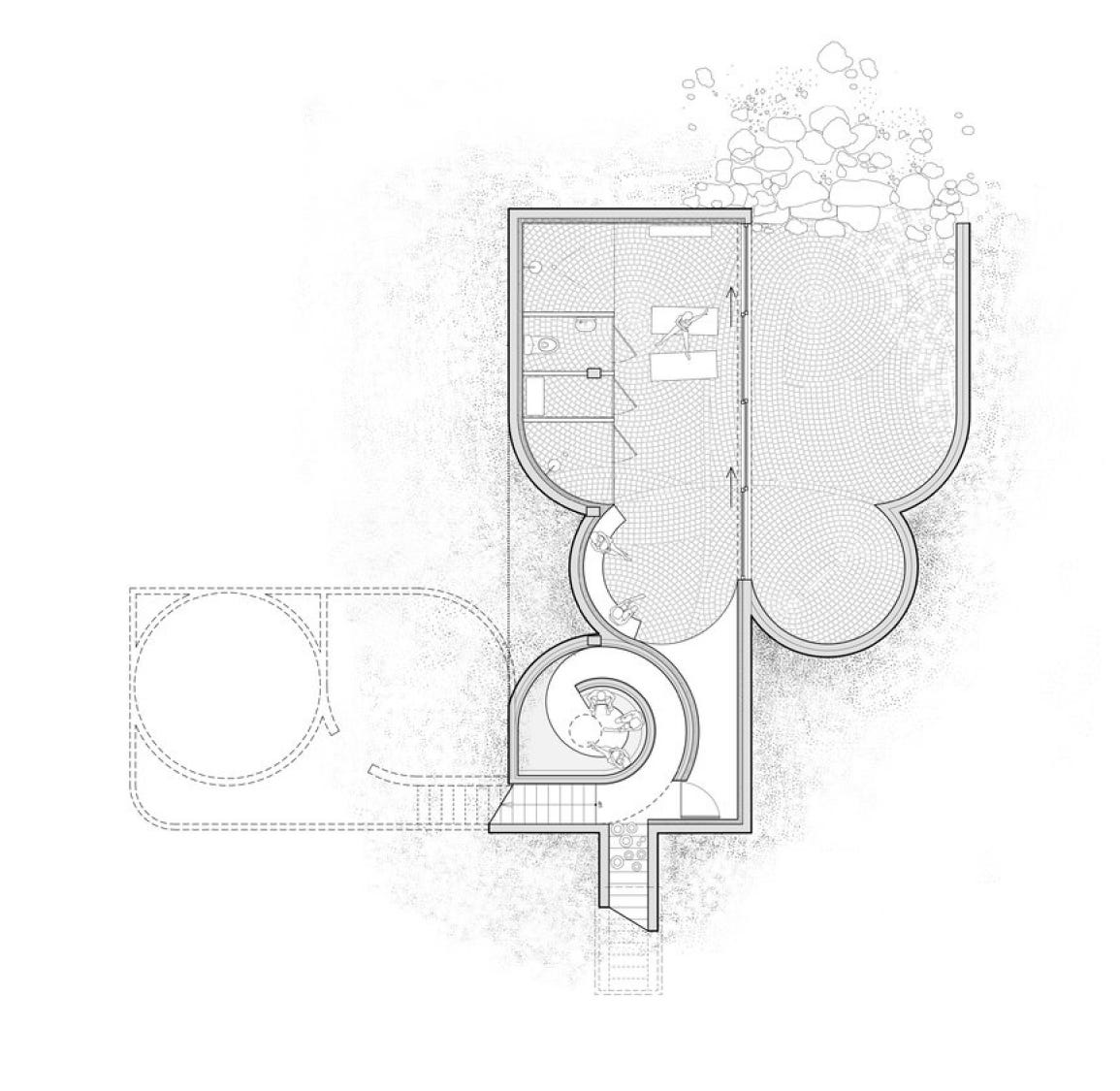

This drawing drawing possesses the most developed mosaic of an plan I have ever seen. In the upper-right space, the stone patterns emerge from the curvature of the walls. This development allows the mosaic to transcend it’s role as an aesthetic tool. The mosaic interacts with the architectural form in a deeper way, almost becoming apart of the entourage.

On a Synthesis

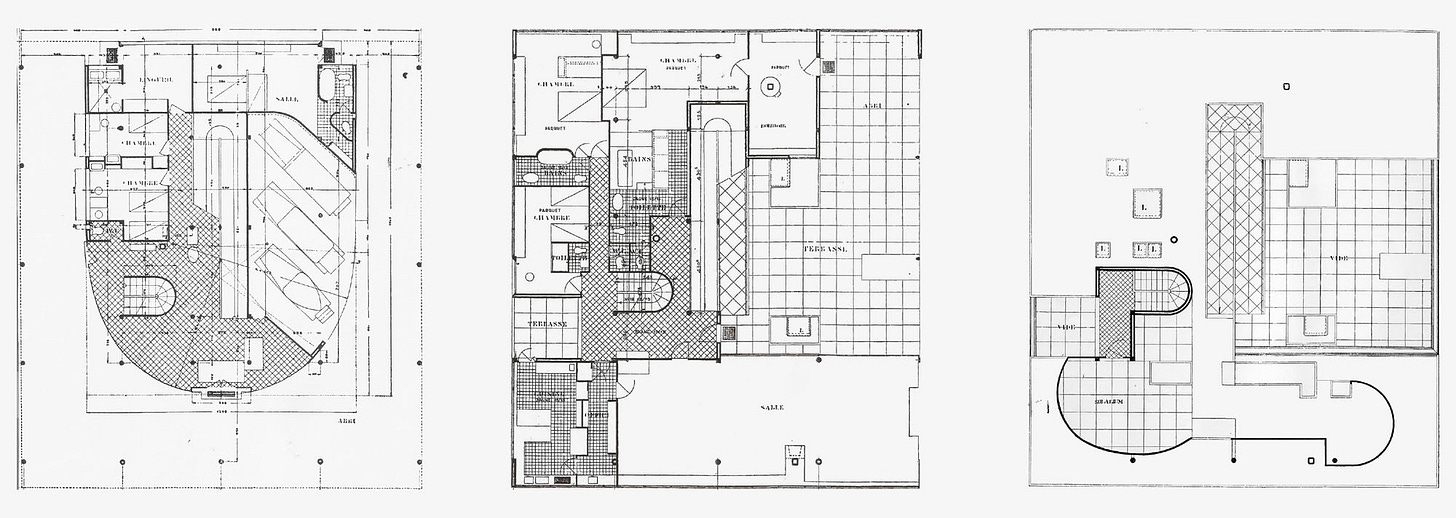

I choose to write about these two concepts together because of this finding: one can track the development of the plan techniques through the history of spatial conceptualization. Essentially, the first drawing technique, poche, was most developed during the second spatial concept, Architecture as interior space. In the modern era, architecture became dominated by function over form, thus, floorplans became primarily about entourage. In Corbusier’s drawings of Villa Savoye, the poche is lost in the see of entourage. The mosaics exist strictly to differentiate spaces.

In previous epoch’s the drawings were dominated by a single technique. Today, the profession is healthy and pluralistic. Thus, each of the techniques have a place and should be represented in drawings. I find plan drawings to be most beautiful when each of the techniques work together to communicate a cohesive idea. In today’s climate, one should think twice about subjugating one of the techniques as was done in previous eras. Thus, the goal of plans should be to elegantly communicate a spatial concept using the techniques of poche, entourage, and mosaic cohesively.

Thank you for reading. Please consider subscribing.

From Giedion’s “The Beginnings of Architecture” published in 1957

I am channeling a Paul Dirac quote from his 1963 article for Scientific America, “The Evolution of the Physicist’s Picture of Nature” which reads: “It is more important to have beauty in one’s equations than to have them fit experiment.”

Are there any modern buildings/architects that build buildings like these?