Understanding Tectonics - 1

“Through tectonics, the architect may make visible, in a strong statement, that intensified kind of experience of reality which is the artist’s domain-in our case, the experience of forces related to forms in a building. Thus, structure, the intangible concept, is realized through construction and given visual expression through tectonics.” - Sekler

Tectonics is a term that gets thrown around in the discipline often. I still do not understand what it means exactly.

It is typically defined as ‘the way architectural elements come together/intersect/join.’ okay, fair enough I guess, but as far as architectural definitions go, this is extremely weak. There are so many unanswered questions here. Is there such a thing as good or bad tectonics and if so, what makes it such?

Take a similar architectural concept such as ‘composition’ as a counterpoint. Composition refers simply to the arrangement of things, but the term has been broadly explored in the field. So much so in fact, we understand how compositional trends have changed throughout history and most designers can intuitively distinguish between good and bad composition. We understand the various types of compositions, and we have assigned terms for them such as linear, radial, dynamic, static, loose, clumsy, or rigid. When talking with designers, I implicitly expect a mutual and rich understanding of the term and its complexity.

The same could not be said about tectonics. Designers are not expected to understand the term beyond the shallow definition given above. This is especially problematic because tectonics is one of the only aesthetic categories to which architecture is uniquely suited for exploration. Painting, digital art, graphic design, and most relief work have no tectonic expression. Even sculptures which necessarily have tectonic expressions are limited due to their scale. Architecture, however, is large and complex, with massive structural systems and rigorous construction techniques, thus requiring a deeper tectonic reconciliation.

I hope to explore ‘tectonics’ in a series of posts analyzing various texts on the term to better understand it myself and to make the term more accessible to those who share my confusion.

I will be starting with Sekler’s 1965 essay “Structure, Construction, Tectonics”. This essay underpins most contemporary discourse on tectonics and thoroughly pulling from classical sources. I hope to expand both forward and backward in time until I feel comfortable with my understanding of the term. If you have suggestions on other readings, please dm me, or list them in the comments. Thanks, and take care.

There are a few sections of the Sekler essay, the first is an explanation of the relationship between architectural experience and linguistics. Included was a reasoning for the essay itself, expressing that developing an understanding for the term ‘tectonics’ as it varies from similar concepts like structure or construction would “increase clarity in a very limited area.”

To Sekler, these terms represent distinct components in the way architecture interacts with the physical world and how we perceive this interaction. These terms are also dependent on one another and act in sequence.

Sekler chooses to define these terms intuitively, by analyzing how these terms are used, and how their uses differ from one another. This is not common in architecture theory for a few reasons. First, defining words based on how they differ from other words is an oversimplification of a structuralist analysis and architects are generally too practical to bother with such sophistication. Second, referencing how words are used colloquially is also uncommon in the discipline as we remain quite insulated and prefer to use our own terms. In fact, you will often see theorists appropriating or sometimes even inventing words to fit a desired and pre-proposed definition.

For example, the word “elegance” has been borrowed by individuals such as Schumacher, Picon, and Scott Cohen, who were looking for a term which fits a specific definition, a definition that is far richer and complex than what is colloquially used. Elegance was the closest word to what they needed, so it was used, mostly disregarding its colloquial usage.

The same could be said with Lynn and Deleuze’s, use of “Fold”, Venturi’s expansion of the word “Contradiction”, Semper’s use of “Bekleidung”, or Burke’s unfolding of the “Sublime”. Many more examples exist, in architecture and in philosophy, I promise.

Back to Sekler.

Sekler noted that the use of term ‘construction’ seems to refer to a ‘realization of a principle or system,’ often constructed by a person. ‘Structure’ on the other hand, is the abstract concept, system, or principle, of arrangement of forces or contexts. A structure could be an arch or a vault. Notice how structure does not necessarily refer to a specific vault or arch, just the abstraction notion of one. This could not be said about construction which refers to specific manifestations.

The quality of an architectural intervention is dependent on both the structure that is chosen and how it manifests as a construction. A well-chosen structure does not imply proper construction and vice versa.

Sekler then uses this framework of definitions to define tectonics:

“When a structural concept has found its implementation through construction, the visual result will affect us through certain expressive qualities which clearly have something to do with the play of forces and corresponding arrangement of parts in the building, yet cannot be described in terms of construction and structure alone. For these qualities, which are expressive of a relation of form to force, the term tectonic should be reserved.”

I apologize for bringing Kant into yet another post, but the precedent set in his aesthetic writing is too useful to ignore (sorry to those who have commented on this, and thanks for reading). Kant’s writing on aesthetics sets a useful precedent for the categorization of various aesthetic attributes. Kant focused on the beautiful, sublime, good, agreeable, and more. I discuss more about these distinctions in my last post.

Sekler’s ‘tectonic’ interestingly fits neatly into this framework as new aesthetic attribute which acts independently to the other terms Kant proposes and is mostly unique to architecture.

To outline these terms clearly according to Kant with the addition of Sekler’s Tectonics:

Good: Good is what pleases through its ethical argument or utility without an appeal to beauty, often based on empirical studies. In architecture, one can imagine that a concept may be morally noble and this is pleasing to observe.

Agreeable: The agreeable is that which pleases the senses completely devoid of a cognitive judgment. This is more subjective than the other terms, including people’s inclination to certain colors or textures.

Beautiful: The beautiful pleases universally without bias by the perceiver, devoid of concept. beauty is not a property of objects but a judgment: it is the experience of disinterested pleasure produced when form induces a free and harmonious play between imagination and understanding, felt as universally valid despite having no rule, concept, or purpose.

The three terms given above represent independent parameters useful for judging an object. For architectural analysis, Sekler’s tectonics fits nicely into this system.

Tectonic: The pleasure that arises from observing the play of forces and corresponding arrangement of parts.

Today, tectonics differs from the other terms because it does not include an inherent value distinction. The beautiful, good, and agreeable are all positive terms. Tectonics refers to a category and is too complex for a simple good-bad, agreeable-disagreeable, beautiful-not beautiful spectrum. This was not always the case, as in antiquity, a firmness or plausibility in structure was seen favorably. Thus, tectonics was explored only in its goal to make architecture appear strong and stable.

Nowadays, designers are more interested in a broader range of tectonic expressions, including precarious looking arrangements of structural elements to evoke a more diverse set of feelings.

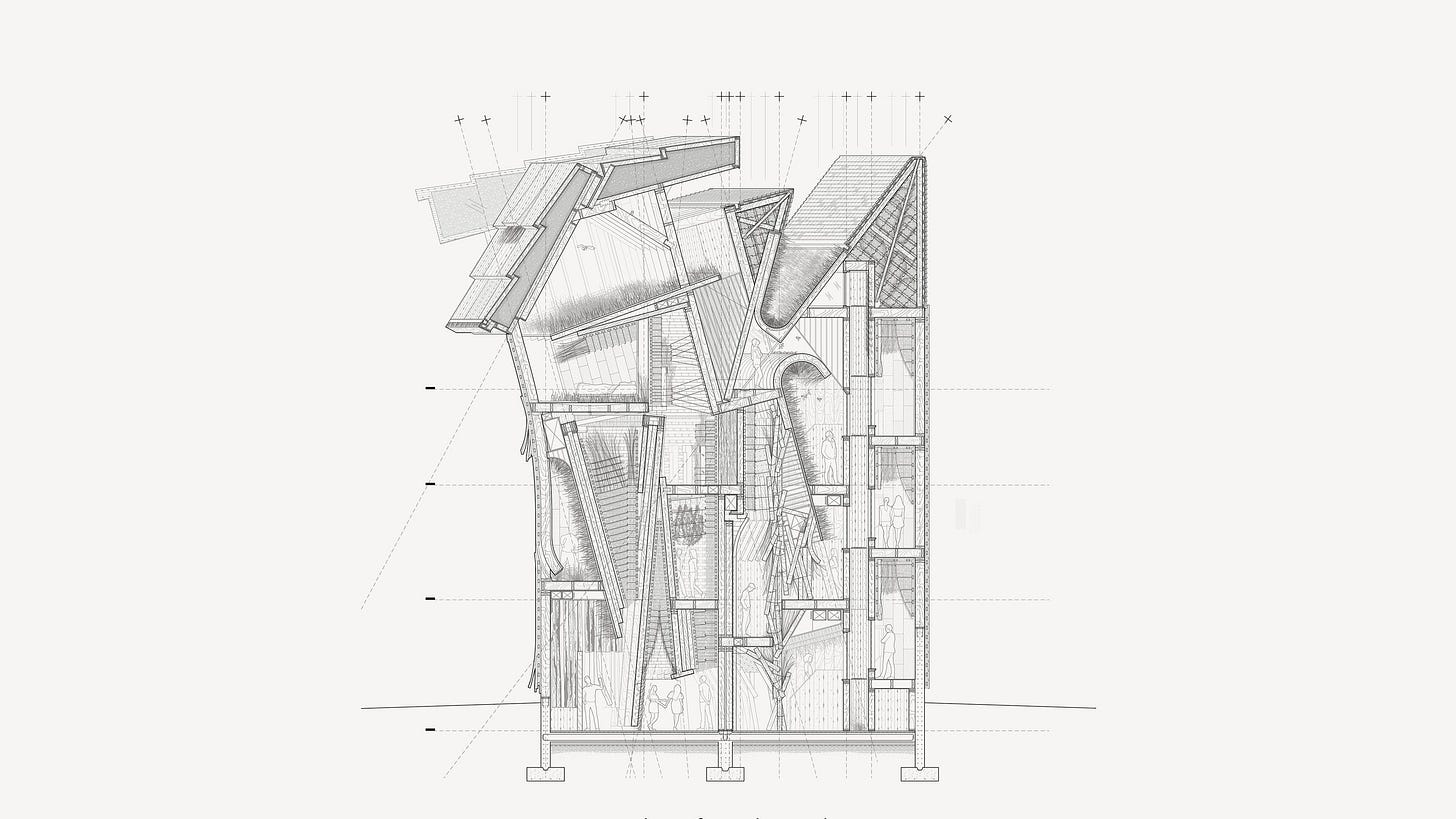

Take the postural studies of Jimenez Lai, or the clumsy tectonics of Kyle Troyer’s thesis work for example. Jimenez Lai is deeply interested in tectonics and manipulates structural elements to mimic various human postures. Most designers who have used Pareidolia do so with form, but using this technique to develop tectonics is fertile territory.

Additionally, the uniqueness of Troyer’s tectonics comes from the reconciliation of an informal or clumsy construction detail, with a spatial organization based on Venturian juxtaposition. That is, overlapping and contradictory parts and spaces with clashing wills. The result is a tectonic reading not based on physics or structural principles, but instead, derived from compositional and construction techniques.

Tectonic expression is sometimes concealed as well. For example, The use of the baby in the below video is evidence of concealment of tectonics. This technique was used in sculpture but was only later adapted for architectural use. Today, I am reminded of the House of Horns, by WOJR, where rounded marble sculptures are used to hide structural function (I think).

On Phenomena

Sekler is quite clear that tectonics is not a simple attribute of architecture, but something that emerges in the act of perception from the legible relation between structure and construction. Today, however, such experiential interpretations are often frowned upon in architecture. Designing for specific effects or phenomenon is often dismissed as theoretically unreliable. This occurs for a few reasons, but from my understanding, it boils down to experience itself being understood as historically conditioned, culturally mediated, and impossible to stabilize as a foundation for architectural meaning.

During the time that Sekler published this essay, many prominent theorists were displacing experience from architectural discourse. Whether or not they were correct in doing so is a different question that I do not feel comfortable attacking in this essay. Nevertheless, it occurred and this anti-phenomenological sentiment persists today. The figures I associate with this trend approached this differently, but their effects were the same. Peter Eisenman is the first name that comes to mind. He was willing to consider architecture as pure formal exercise, displacing the subject from its privilege.

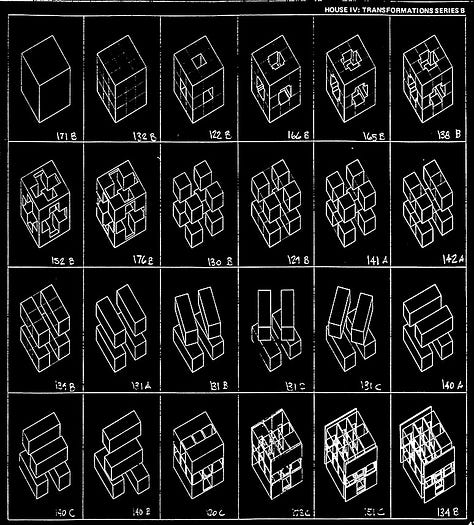

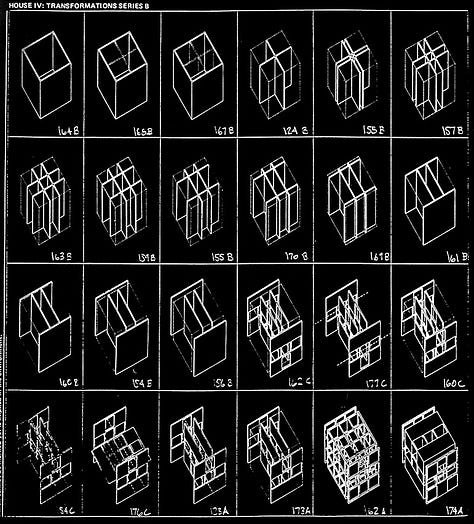

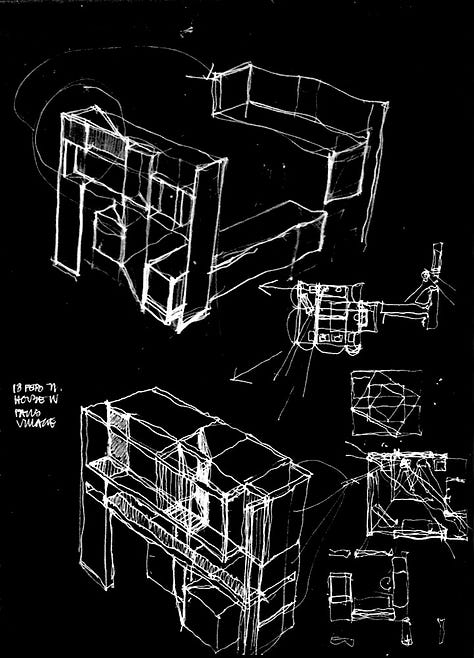

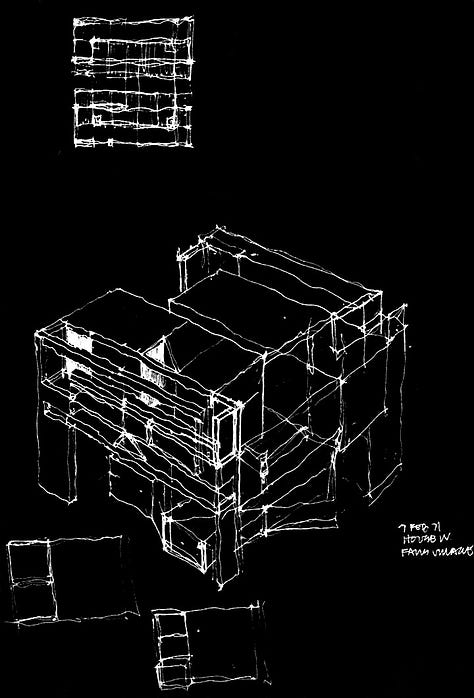

Eisenman writes in his description of his “House IV 1971” Project

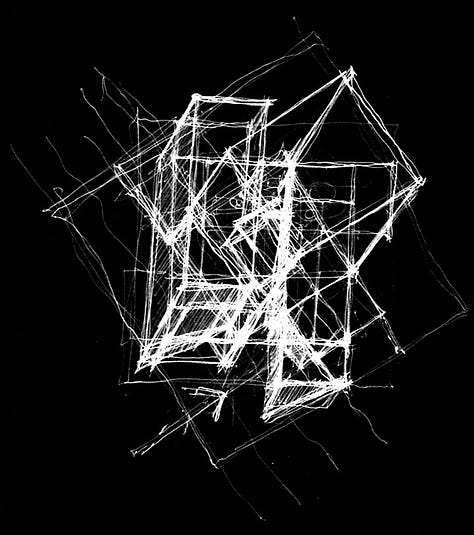

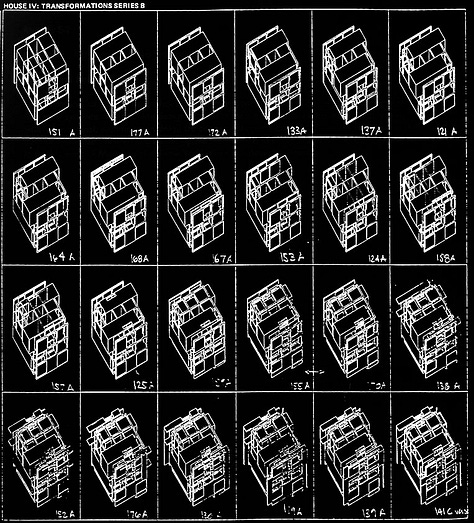

“In House IV, a limited set of rules (shift, rotation, compression, extension) was applied to a limited set of elements (cubic volume, vertical planes, spatial nine-square grid). This transformational method establishes a code of spatial relationships within the syntactic domain of architectural language. The set of diagrams thus produced is recorded as both substance and indexical sign, which shift the focus away from existing conceptions of form in an intentional act of overcoming materiality, function, and meaning.

The transformational methods employed in House IV were specifically constructed to be largely self-propelling and therefore as free as possible from externally determined motives. A “logical formula,” that is, a step-by-step procedural model, was established. Then basic elements such as line, plane, and volume were set into motion, resulting in an object that appeared to “design itself.” Whether the result would be architecture or would have architectural features such as plan or façade was not a consideration of the process or a criterion for evaluation. In this sense, the problem was not to design an object but to search for and establish a transformational program free from traditional authorial constraints.

In House IV in addition to the investigation of an autonomous process, the challenge to the hierarchical nature of configurational systems was extended to a certain dialectical relationship in architectural form, specifically the implicit hierarchy of the “favored partner” in dialectical pairs. Thus, if frontality/obliqueness is taken to be one such dialectic, with frontality the preferred point of view of modernism, in House IV the oblique view was equalized in importance with the frontal. Similarly, the simultaneously perceived was equalized with the sequentially perceived.”

This formulaic process became even more popular in the nineties when the discipline because obsessed with software. The process has remained popular today especially within certain academic programs, specifically, Penn, Sci-arc, Pratt, RPI, USC, and certain camps at the GSD. This has also been pushed forward in the theoretical writing and work by Mark Foster Gage, Graham Harman, and others under the camp of OOO.

Additionally, figures like Koolhaas also played a hand in the devaluation of experience in architecture, focusing more so on program, infrastructure, politics, and economics, treating buildings not as instruments of experience but as condensers of global, organizational, and demographic forces.

All of this to say that the study of tectonics to Sekler requires an engagement with the human subject and its experience which is unpopular today.

Troyer’s work is particularly interesting because it tries to develop a tectonic study devoid from experience.

From his thesis description:

“While the project capitalizes on the usage of the terms clumsy and odd, these two aesthetic categories are meant to be interrogated on a technical level to guide material explorations as well as uncommon spatial and organizational principles; the project is less interested in their ability to provoke feeling and affect. The thesis explores the design of a technique rather than a finished building.”

What this brief survey suggests is not that Sekler’s conception of tectonics is obsolete, but that it occupies an increasingly uncomfortable position within contemporary architectural discourse. If tectonics, as Sekler defines it, requires an engagement with experience, then it inevitably reintroduces the question of the subject at precisely the moment when the discipline has worked hardest to displace it.

Thank you for reading, have a great day.

To me, tectonics carries a primordial connotation. The word summons images of primitive structures, for example the trilitic system, elemental assemblies of mass and load. There is a sense of gravity to it, both literal and symbolic, as if tectonics belongs to the origins of building rather than its refinements.

Super interesting reading and great references.

My understanding and apparently application of tectonics is much simpler (according to a good friend and very good architect) and that is he says: that either I do most of my projects in a tectonic way or they appear “stereotomic”.

This comparison helps to understand tectonics as the opposite of mass/massive, grounded even contextual or situational in stereotomy.

Therefore tectonic architecture is lighter, not just in weight but also visually. The structural elements are often apparent or exposed.

The über example could be the Pompidou or any early Norman Foster building. The Eisenmann house you mentioned is amazingly tectonic because the walls are structure as well as organizational.

I tend to have the result of both tectonic and stereotomic structures but the approach is tectonic because I use the structure as part of the design process from conceptualization to execution.

Thanks! Cheers from Mexico!

H.